COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

The phonograph needle ground into its stop groove. Armando Dominguez’s sweeping Mexican Ballad Destino finished establishing the mood. The walls of the room were a montage of pencil sketches and paintings. Salvador Dalí paused as he completed narrating the visual sequences to this song, and told a journalist at the Disney Studio in 1946 that everything he ever painted will be in it, all his pictorial concepts -- the melancholy of space, dissolving images, hallucinations of man and landscape.

Just as with Bauhaus abstract painter and animator Oskar Fischinger who worked on Pinocchio and Fantasia, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to invigorate the artistic boundaries of his studio. The two met at a party that WB studio head Jack Warner gave around the time Dalí was designing a sequence for Alfred Hitchcock’s film Spellbound. Shortly thereafter, Dalí started work on the Disney lot designing visuals for a short entitled Destino which was intended for inclusion in one of Disney’s anthology features, like Make Mine Music. Walt Disney stated in 1946: “Like the Night On Bald Mountain sequence Kay Nielson designed for Fantasia, I want to give more big artists such opportunities. We need them. We have to keep breaking new trails.”

To the public the name Dalí became synonymous with Surrealism, an art form from the 1920’s derived from the writings and art of post World War One Dadaists. Surrealists drew inspiration from dreams and a study of the Freudian subconscious. Their art was meant to startle and disturb the viewer, not only through abstract technique, but by its primal and arbitrary subject matter. Dalí took these intellectual themes from a decade earlier and by using a more realistic painting technique (one that owed its lineage more to the luminous color and renderings of Jan Vermeer and Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier than the harshness of Max Ernst or André Masson) made Surrealism tangible to the public.

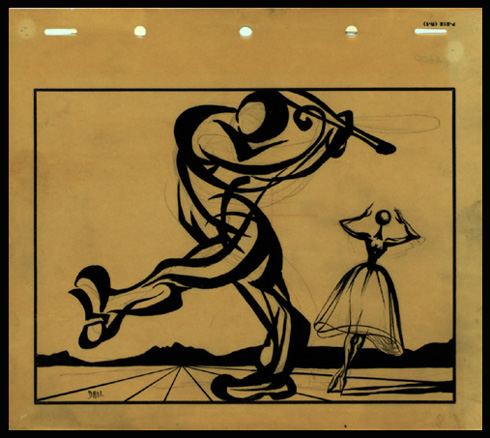

The symbolism in Dalí’s art was uniquely Dalí. It drew from his everyday life and extracted seemingly arbitrary things such as infinite desert plains, marble statues, baseball players, bicyclists or telephones and used them as icons where through their isolation they became symbols for deeper emotional themes. A poetic hieroglyphic where limp watches symbolize the destruction of time and the tragedy of love, an open hand with ants eating at the line of the palm depicts the disintegration of man, a crutch suggests that man can not live alone.

Twenty two paintings and 135 story sketches into the project, Dalí was asked to abandon Destino as the package pictures of the 40s proved financially unsuccessful. It lay dormant for 57 years until Walt’s nephew and executive producer, Roy E. Disney instructed producer Baker Bloodworth and director Dominique Monfery to complete Dalí’s short. They did so with the assistance of John Hench, who along with Bob Cormack assisted Dalí on the original project. The finished film unites Dalí’s surrealist vocabulary to animation and includes five of Dalí’s original paintings.

Walt Disney described Destino as “a simple love story, where boy meets girl.”

An arid dream, a poem -- Dalí’s Destino is a haunted relationship play, where the turmoil of unresolved romance struggles to the mind’s surface. It challenges today the way it was meant to challenge in the 40s, and asks the viewer, and the animation industry, to see beyond conscious commercial possibilities, to blaze their own aesthetic destiny.

Salvador Dalí at work at the Walt Disney Studio, circa 1946 (left).

A Dalí oil painting produced for Destino was later incorporated within the completed short (right).

Seen at the left is a finished conceptual oil painting done by Dalí as inspiration for his Disney short

Destino. At the right, is the Dalí painting as it appears in the film -- with some digital elements used to

extend the perimeter of his painting and with an animated figure and two prop elements.

Three conceptual images created by Dalí in preparation for Destino.

Another Dalí oil painting to which animation of a baseball player and baseball were later added.

All images are © Disney Enterprises Inc.

The author would like to thank Roy Disney, Walt Disney Feature Animation, the Walt Disney Archives and Dave Smith, the Walt Disney Publicity Department and Howard Green, Ray Morton and Dave Koch for their help.

This article is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

THE DESTINY OF DALÍ'S DESTINO

© 2003 Ron Barbagallo

Dalí's Destino played at the Telluride Film Festival and is scheduled to be at the New York Film Festival on October 14, 2003 and the Chicago Film Festival -- sometime in October 2003.

It is scheduled to play the ArcLight Theatre in Hollywood, California on Fri, November 7, 2003 at 6:30 pm and Sun, November 9, 2003 at noon as part of the AFI International Shorts Competition. Admission is $11.00.

At this time, there is no theatrical release date.

A DVD featuring Destino was slated to be released on November 11, 2008 but has been put back in the company's release schedule; it is not known at this time when the DVD will be released. When it does come out it will also include a documentary on the making of Destino featuring John Hench and Joe Grant and two new featurettes: The Disney That Almost Was, an examination of the studio’s unfinished projects and Encounters with Walt, a film about celebrities and artists who were attracted to Walt Disney’s early work.

VIEWINGS OF SALVADOR DALÍ'S DISNEY INSPIRED SHORT - DESTINO

DESTINO CONCEPT ART BY SALVADOR DALÍ

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO: