COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

On October 7, 2005, Wallace and his faithful dog Gromit, the much loved duo from Aardman's Academy Award® winning clay-animated Wallace & Gromit shorts, star in an all new comedy adventure -- Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.

In an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park shares some of his thoughts regarding his artistic influences, how he uses drawing to start telling a story, and what it was like to bring everyone's favorite plasticine duo to the big screen for the very first time.

Nick Park:

It's really a dream come true. Wallace and Gromit were my college creations, and it is quite something to think that they are starring in their first full-length feature film.

I look back on having made the three shorts as if they are, in a sense, like making smaller feature films, so the feature seemed like the next actual step. I guess because I found what was great about working in the medium -- how you can light it, how to do camera work. It satisfied many things for me.

But at the same time I was a bit cautious because sometimes what works in short films works because they are short. I was cautious on how to get there, how to make that step which is partly why we did Chicken Run first.

I was waiting for the right idea to come along that was big enough and simply expansive enough to suggest a full-length movie. An idea that had the potential for an 80-minute film with character development and story but also was inspiring enough to sustain me through for the next four or five years.

Once you decided you wanted to move forward with planning a movie for Wallace and Gromit, how did you start your production?

Nick Park:

After I’ve come up with the initial idea -- you know this whole idea of exploring rabbits -- Bob Baker, the writer and I were sitting in a pub in Bristol and we got this lightning strike of an idea -- what if it were a were-wolf movie, but with a big funny rabbit instead eating vegetables instead of people and develop it for Wallace and Gromit? After that I decided to develop it with a guy I was going to co-direct it with named Steve Box who worked with me on Wallace & Gromit: The Wrong Trousers. He animated Feathers McGraw.

We sat there typing it and as we were typing, one of us would be drawing, or vice versa, or the other one would be making a mock up model in clay while we were writing. So it all went on at the same time.

Then there was a certain point when we stopped writing, where the script becomes very visual and we went into storyboard for most of the writing time actually. We spent a couple of years storyboarding. We'd shoot the boards and then put them into a digital edit system. We put our own voices on, temporary music, some sound effects and edit the whole thing.

It would be very rough, but those storyboards would become our story reel. We’d constantly be editing from that. Redrawing stuff, trying to make acts better, trying to find scene structures that were better. Sometimes we’ll throw out the whole scene and decide we don’t need it or add a scene somewhere. It remains a very organic, constantly rolling process to the end of the movie.

It's like making a sketch, really, refining lines, going back and bringing certain qualities forward, deciding if sometime works or not?

Nick Park:

Yeah, that’s what we show to Jeffrey [Katzenberg] every few weeks. They make comments and our other writer Mark Burton would come in and think up some better lines of dialog. We’d have a brainstorming meeting over a scene and think -- how can we make this scene funnier? How can we make the story point a bit quicker? You know, that kind of thing. It gives an overall sense of the shape of the movie above all as well. Obviously in this kind of filmmaking we can’t afford to shoot stuff we don't use and we did end up not using a couple of minutes worth.

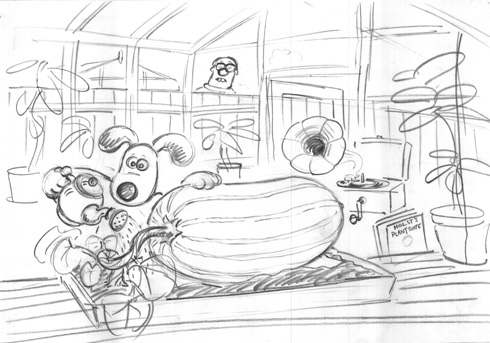

Concept drawing by Nick Park of Gromit in the Greenhouse.

The finished frame of film of Gromit in the Greenhouse.

A camera lens captures a still frame of stop motion animation.

Nick Park directing the very same scene from the above drawing of Gromit in the Greenhouse.

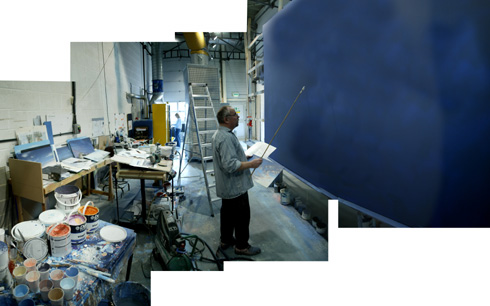

Scenic Artist, Fred Grey reviews the night sky backdrop.

Gaffer, Richard Hosken and Director of Photography Tristan Oliver prep the "Woods" set.

When did you start to take the world of your 2D drawings into the world of 3D claymation? Was it while you were in college creating drawings?

Nick Park:

Yeah. It was really. Sometimes I thought, well, should I do this in 2D? Then I thought it’s such satisfaction making them in clay. The idea that you can make them three-dimensional, so that they had their own natural perspective. You can light it and all. I love that world. There’s a certain other-worldliness. It’s like an almost other reality but it’s not.

And, while I’m interested in clay I think I wanted to take claymation more into the area of story. You know use it for like a bigger thing, than just an animation affect. With clay animation you can treat it like a cartoon really because of all this squash and stretch. Yet you’re working with all these cinematic live action elements, tools and devises: lighting and camera work, drama.

That's why going to film school was so great because it really educated me about movie making. The more films I saw, the more I could learn.

Where there any changes in materials or technology you had to make to take Wallace and Gromit to the big screen? Any changes to the clay you were using for the shorts?

Nick Park:

No, it’s the same old stuff really [a special blend of Plasticine, nicknamed "Aard-mix" which is slightly more durable than ordinary Plasticine]. I was really keen to keep the feeling of the short films in there. I didn’t want to think that just because it’s become a feature film to suddenly get slicker or you know smooth or anything or have another visual quality. I wanted to keep the hand-made quality that’s its always had.

Are your backgrounds still hand-made sets with fully painted backgrounds behind them, or were they done digitally this time?

Nick Park:

No, the backgrounds are all be real sets with painted backdrops. Even if we blue-screened or shot Gromit against a green screen when there’s a real effect in the background. You know like when they’re flying along and stuff like that.

We did use digital technology sometimes to create effects, like fog, you know, and even then we didn't always do that digitally, because you can’t animate fog. The smoke would move. Sometimes after a shot we would take the figures out and do a run where we added smoke. Then digitally lay that in afterwards; or we'd create smoke digitally, like for a kettle boiling or a flame on a cooker.

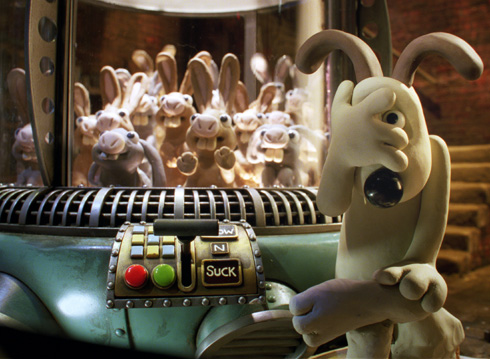

At certain times, some of the bunnies in the Bun-Vac 6000 were put in digitally. But we were keen that they would look like they were made of plasticine.

Directors Nick Park (left) and Steve Box (right) reviewing storyboard panels.

How would you describe your take on storytelling? What sort of things did you look at while growing up that you feel influenced you as a filmmaker?

Nick Park:

The Wallace & Gromit movies I made were always referencing other film genres outside of animation. Films that I loved all the time. Hitchcock films, film's like (David Lean's) Brief Encounter and I equally love the work of Chuck Jones, Tex Avery, Tom and Jerry cartoons and Disney films. I grew up on all these films.

I’ve always loved slapstick comedy. I love Buster Keaton and all the Laurel and Hardy films. Maybe that’s where I got Gromit looking at camera and giving us kind of a knowing look to the audience. Maybe from Oliver Hardy the way he would seem so "give me strength" -- you know, put upon, looking for sympathy.

I’ve always loved book illustration as well, and collected comic books. In the 70’s and 80’s I read graphic novels, like Hergé’s Adventures of TinTin and the illustrated books of Raymond Briggs. He did a book called Father Christmas and Fungus the Bogeyman which were popular in the UK. I love that graphic and chunky style that he had where everything is rendered. He also did The Snowman, which was later turned into animation.

I always loved those 1950’s shapes, all post World War II. I love a lot of that stuff, too. I used to watch Ray Harryhausen's Mother Goose Stories. He did one called Hansel and Gretel (1951) years before. I love that and that kind of holiday animation that was on TV.

A lot of ideas I have are inspired by those kind of things, those kinds of aesthetics.

I guess it’s the satisfaction of everything I love coming together, you know, Jules Verne stories, H. G. Wells, TinTin Adventures and Laurel and Hardy comedy kind of all coming together but with the atmosphere of a Hitchcock movie.

What is the role of drawing in your films?

Nick Park:

I always start off by drawing. I start off with visual ideas. It’s what started off my film

A Grand Day Out. I started drawing this rocket, and I thought it would be great to just build to it. That’s one of the sort of things that attracted me to 3D really. The chance to build something like this rocket in this big cigar shape and cover it with rivets.

Years ago, at college, a lot of my illustrations, the ones I did when I wanted to illustrate books and do the stories were done as just illustrations. So, I've always started off by drawing, drawing nice shapes really that I liked.

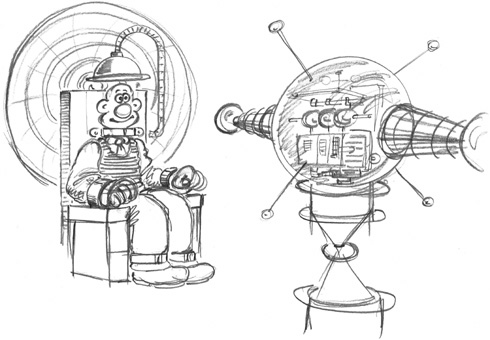

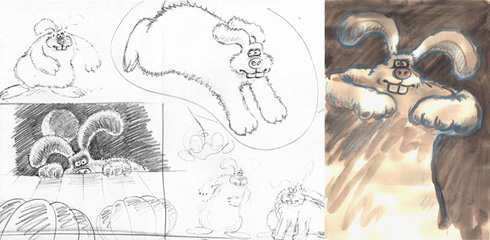

Concept drawings and story sketches by Nick Park and Steve Box. All black and white sketches

above are by by Nick Park. Color sketch, second from the top, is by Steve Box.

Key Animator, Ian Whitlock posing the rabbits for a shot.

Character designs of the Were-Rabbit by Nick Park (top).

Color concept design and storyboard of Were-Rabbit on the run by Mike Salter (bottom).

With Peter Jackson having made the decision to use digital technology to create King Kong in his upcoming film of the same name, did it ever occur to you to do the same? In the original film Willis O'Brien used hand made 3D animation to create Kong.

Nick Park:

It’s funny that you should mention that, because we could have done our Were-Rabbit using CGI because you can do such great fur and everything. But we just chose to do it more in keeping with Wallace & Gromit and do it in the old way -- make a big fur puppet and animate it, harking back to King Kong because of the sympathy the animator was able to put in his eyes, in his facial expressions. He was the force of antagonism, a beast; and yet you felt so strongly for him. We were trying to tap in on that kind of quality and didn’t mind if the fur was a little moppy or twitches a bit, like in King Kong, really.

Did you base the characters of Wallace and Gromit on anyone in particular? Did you have a dog?

Nick Park:

No, I never had a dog. Gromit is the only family dog I’ve ever had.

You've known Wallace and Gromit for sixteen years now. Was there anything about them you didn't know, that you learned about them while making the movie?

Nick Park:

[laughs] I suppose there is, because in a way they sort of write their own stories these days. It’s the beauty of having established characters. They take on a life of their own and you’re waiting for them to tell you the story in a way.

I think, if anything, I learned just how far I can you push them. That in their own way, they're an elderly couple. They know each other so well, a love/hate relationship. But it's a deep-seeded love relationship and at the end of the day, they will look out for each other. So we were able to push Gromit’s loyalty to the extreme. And, also, it occurred to me while making the film, that Gromit is always trying to change Wallace, you know; Gromit had to face [the question] how much can you change someone?

AN INTERVIEW WITH NICK PARK,

Creator of Wallace and Gromit and Co-Director of DreamWorks and Aardman's

WALLACE & GROMIT: THE CURSE OF THE WERE-RABBIT

MAKING HIS MARK IN CLAY

© 2005 Ron Barbagallo

Nick Park poses with his plasticine creations -- Wallace and Gromit.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit makes its

US debut on Friday, October 7, 2005.

All images are © DreamWorks Animation SKG and Aardman Features. Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit is distributed by DreamWorks Distribution LLC.

The author would like to thank Nick Park, Fumi Kitahara, Ella Robinson, Ray Morton and Dave Koch for their help.

This article and interview is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO: