COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

Images are courtesy of © Marc Wanamaker/Bison Archives

This article/chapter is owned by © Steven Bingen.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this writing without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

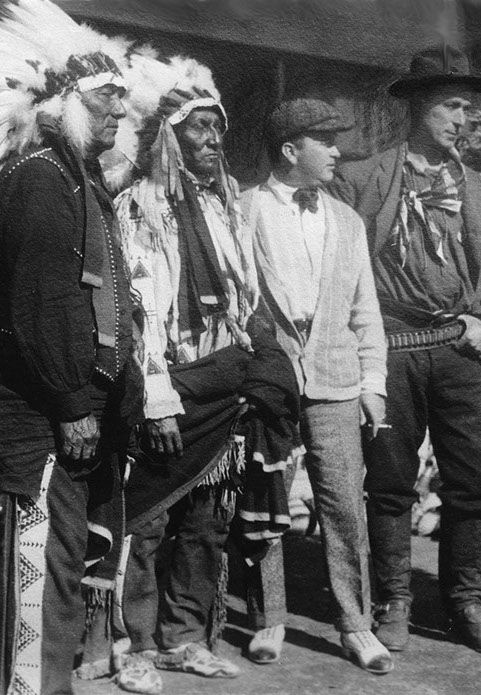

Thomas Ince, flanked by cowboys and Indians, including leading man William S. Hart, who stands to his left. All look to the future. (1914)

HOLLYWOOD's LOST BACKLOT, 40 Acres of Glamour and Mystery

Chapter one, the man with the Megaphone

© 2018 Steven Bingen

PART OF the Lost and FOUND series FROM

THE RESEARCH LIBRARY AT ANIMATION ART CONSERVATION

The story of human civilization in America starts with the arrival of the Native Americans. Not to make comparisons, but so too does our story.

The Indians in our story were real Indians, maybe—as Oglala extras were, in fact, available to a particular producer filming a particular movie here more than a hundred years ago. If this was the case, the Indians would have brought their own costumes, although these same Indians were apparently not above raiding the wardrobe and prop bins back at the studio in search of colorful pieces with which to add a dubious authenticity to their buckskins.

However, these Indians may actually have not been Indians at all, but rather Caucasian, or Mexican, or even Asian actors that day—awkwardly rowing birchbark canoes up Ballona Creek—in which case these ersatz Native Americans would have been wearing dime- novel costumes from those same bins and itchy, braided wigs.

In any case, the creek itself, if nothing else, certainly was authentic. It turns out that that creek had been selected because the Los Angeles River, and specifically the terrain around it, was unsuitable and because the Pacific Ocean, regrettably, was the only body of water fronting the studio that the company had driven out from.

The year was 1915, and a movie, the first of thousands to be birthed on that spot, was being made. A hundred- plus years later, no one seems to even remember what the title of the film was. The important thing to remember here is rather that those possibly apocryphal Indians floundering across those waters that day were observed by a very interested spectator.

His name was Harry Hazel Culver. And he liked what he saw.

Culver was a real estate developer from Nebraska. He had appeared in California in 1910 with ambitions of creating a community with his name on it, and at this point he was well on his way to making those ambitions happen. Although “Culver City,” as it would come to be known, with its original population of 550, would not be incorporated for another two years.

Culver was more interested in the men on the bank filming the tableau than what was actually being filmed. He had noted with a most keen interest recently the proliferation of movie crews that had been marauding across Southern California in recent years. Most respectable and conservative businessmen of Culver’s standing were disdainful of the movies and the people who watched them, and most certainly of the people who made them. But Culver, with his middle- class, Midwestern sensibility, very much liked going to the photoplays, liked seeing them with audiences of laughing immigrants, many of whom, he was smart enough to realize, would eventually be joining the middle class themselves and hopefully, soon after, buying his houses.

He also liked, within reason, the people who made those movies. Many of them were themselves immigrants, or the children of immigrants: Eastern Europeans, possibly even Jewish. And make no mistake, they were loud, loud and boastful, and crass and profane—East Coast types of people to be sure. Yet one had to hand it to them: They were inventing an entirely new industry. And no one in Los Angeles, except him, seemed to bother to notice this.

Many of these picture people were already clustered in a nearby village named Hollywood, yet the residents there, strict prohibitionists, treated them like they all suffered from smallpox. Hollywood had even gone so far as to scornfully pass laws making it illegal to show movies publicly within that community.

Harry Culver walked over and struck up a conversation with the man in charge of the little crew. He found that man easily enough. He was the fellow who yelled the loudest—and through a megaphone yet. Culver convinced that man that his community, when created, would welcome—indeed would provide completely free, or at least on a deferred payment plan—real estate to any producer willing to relocate to the Ballona Creek area.

That man in charge, the man with the megaphone, was one Thomas Harper Ince.

Ince was a man whose importance to the early development of the motion picture industry cannot be overstated. Born in 1880 of English stock in Rhode Island, to a show business family which Culver might not have entirely approved of, Ince had drifted into the fledgling film industry in 1910—initially because he had a young family to support, and because an old theater colleague, one Joseph Smiley, was willing to recommended him for a job.

His early days in the movies were spent as an actor, but Ince, among the first of millions to follow, quickly fell in love with a business he had originally seen only as a get- rich- quick scheme. He quickly realized that the real way to be creative in the movies was on the other side, the narrow- concentrated side, of that megaphone. “The story-teller has never found so pliant a medium for his interesting occupation as the screen,” he would pompously pronounce in 1916. “Drama has long been a thing of the artificially lighted stage, and it has been so bound in by time, by the mechanical exigencies of scene and costume, by the limit of human adaptability and endurance, that it is little short of marvelous that such complete representations have been made.”

So Ince rapidly became a director, and then one of the first director- producers. What’s more, he turned out to be a keenly creative producer with an eye for story, location, and visual composition, and for spotting talent.

He also created, not incidentally, the business model that movie studios, to a large part, still operate by today. Before Thomas Ince, those movie studios, if they could even be called that, were disorganized and hurly- burly and chaotic. There was no cohesive production process in place—so everyone, from the actors to the visiting landlord shuffling around looking for his rent, might be asked to pitch in, moving sets or carrying equipment—all just to try to get the damn thing done.

Compounding this chaos, there were usually no scripts, or scenarios as they would have been called then, to determine what the story was, and no one on the payroll to write it all down anyway. Usually, the on- screen action ended up being improvised on the set—also improvised—and the whole tottering, unwieldy process would lurch along, from inception to distribution, stumbling against all reasonable odds from one to the other, with no apparent plan in mind along the way.

So it was Thomas Ince who decided that there had to be another way. He based his ideas about film production not on the model of how films had chaotically and haphazardly been glued together in the past, but rather on that of the heavy industry of Detroit, where automobiles were constructed from first nut to final paint job in one place, with the same people doing the same job on each vehicle that ultimately rolled glistening out the gate.

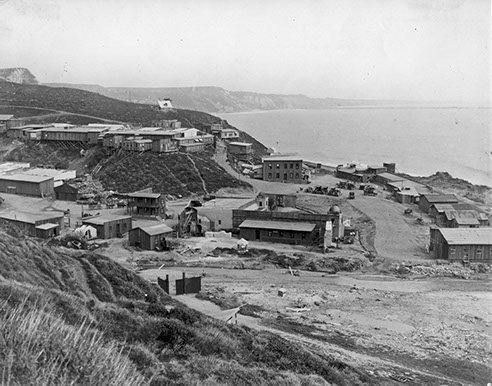

Ince built his first studio, eventually called “Inceville,” in 1911–12 at the end of Sunset Boulevard on the Pacific Coast Highway in what is now the Pacific Palisades. Filmmaking concepts that later became common at all the studios were first implemented in this foggy, windswept crevice above the Pacific Ocean.

However, in spite of the grandeur of its conception, Inceville in execution resembled nothing so much as “a sleepy, dirty western town—scattered buildings, of plain boards, and rut- worn roads leading into the hills,”2 as actor John Gilbert unsentimentally remembered it. Yet it was here that the organized, departmentalized, and later unionized concepts that would turn studios into empires were created. It’s also worth noting that it was here, for the first time, that standing sets were intentionally left standing, on a so- designated spot at the back of the studio grounds, effectively making Ince the father of the backlot—although father Ince once fibbed in an interview that he, in fact, seldom reused sets, believing, he said, that they would be recognized by audiences.

Ince is also credited with inventing the title of “production manager” and formalizing the functions of the editor, screenwriter, costumer, accountant, and even director (the director until this time had been forced to assume the responsibilities of all the above), which, as he had hoped, enabled his hardscrabble little studio to make more than one film at a time. A film industry first—in what was not yet an industry at all.

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO:

Filmmaking is the process of turning money into light, and back into money again.

— John Boorman

Inceville didn’t last long. Although he created stars and directors, and even the very concept of stars and directors, and produced hundreds of films on the site, Ince knew that the property, if not the production methods created there, was too distant from the rest of the city to ever be practical, and the dampness and gloom that washed in from the ocean was hard on both the sets and on the actors using them. What’s more, the wind often blew that dampness and gloom as well as, even worse, sand into the laboratory equipment, making much of the precious film—the result of everyone’s efforts—being processed there that day unusable.

In 1915 a fire nearly burned the studio down, and early the following year, a second, more extensive blaze destroyed some of the property as well. Ince, who at the time was finalizing a deal for a venture called the Triangle Film Corporation with fellow producers Mack Sennett and D. W. Griffith, was understandably considering a move, perhaps to Hollywood, when, megaphone in hand on the banks of Ballona Creek, he happened to meet Harry Culver.

Post- Ince, Inceville continued to be used as a studio by, among others, Ince discovery William S. Hart and Robertson- Cole Pictures until 1922. Two years later the remaining facades, which must have looked like an actual Western ghost town by this point, caught fire one last time, scattering their blackened dust into the ocean.

Inceville is where many of the concepts by which motion picture studios still operate were first implemented. Behind the clapboard bungalows and false fronts to the south is Santa Monica Bay. (1919)

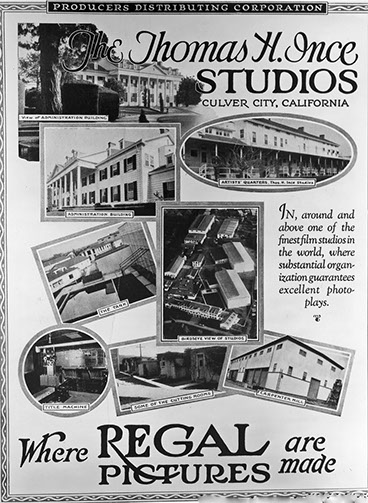

Ince and his partners built a new studio in the still unincorporated “Culver City” in an appropriately triangular shape fronting Washington Boulevard. Some of the property had already been used as an army barracks, but the impressive Corinthian- columned colonnade facing the street was probably Ince’s idea. The producer wanted his next kingdom, unlike his last, to be impressive looking, at least from the street, as well as functional. In March of 1916 the studio was officially opened.

The colonnade is still standing, but the partnership and Triangle Pictures was not to be long- lasting. A major point of contention between Ince and the company was the studio itself, which Ince owned, as per his deal with Culver, but which management asserted belonged to the company and even listed as a company asset in their stock offerings.

The chaotic-appearing “stages” at Inceville were open to accommodate available light, which was often in short supply on the hazy Pacific coast. (1913)

In 1917 Ince sold his interests in Triangle, and reluctantly, in the Triangle Studio itself. The studio was purchased in 1918 by Goldwyn Pictures, which, through another siege of mergers and takeovers, eventually emerged as the mighty Metro- Goldwyn- Mayer, which it would remain until 1986. Today the property is Sony (Columbia) Studios. As noted, the colonnade is still there.

Harry Culver, standing on the sidelines during all of this blood sport, undoubtedly realized that Ince, down but certainly not yet out, would eventually need yet another property, this time to be called, finally, Thomas H. Ince Studios. More than happy to oblige, he offered him a 14-acre property that was an almost literal stone’s throw from the Triangle lot.

That property had, since 1781, originally been part of El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, but it wasn’t until 1821 that Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes was created on the grounds. The name translates as “corner for the oxen,” because of a box canyon in which livestock could be herded. The Higuera family, which included the son of a former alcalde (mayor), claimed most of the land. In 1872 a United States patent listed the property as belonging to Francisco and Secundino Higuera and consisting of 3,100 acres.

According to historian Jacob N. Shepherd III, Achille Casserini, a Swiss immigrant, acquired at least some of the property, probably around the turn of the century, which would become the 40 Acres backlot, although Culver, at this time, was only interested in getting Ince to sign on the dotted line for the primary front lot parcel.

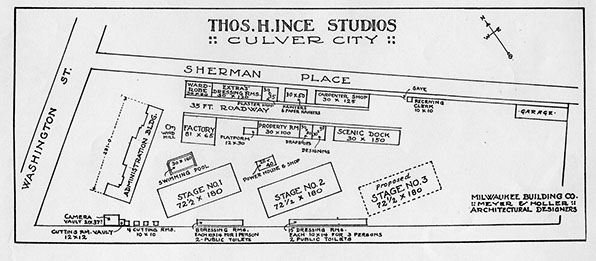

According to the document above that dotted line, which was recorded at the Los Angeles County Hall of Records on November 4, 1918, Culver agreed to build, and to pay for, the construction of the first three buildings on the property, namely what would soon be known as the Mansion and the first two stages, as well as “such other buildings” as needed, to the sum of $132,000. In return, Ince would lease that property for five years for $90,000. He was also given the option to purchase the lot outright anytime within the first three years for $145,000, an amount that any rents paid to Culver to that point would be applied against.

The new Triangle Studios in 1916. Note the prominence of Ince’s name in the signage. The street running along the side of the lot on the left has since been swallowed up by studio expansion, but significantly enough, was named Ince Way.

The press, however, probably being fed inflated information by Ince’s publicists, got most of the details wrong. For example, Moving Picture World reported in December 1917 that the price of the property was $25,000 and that “the plant to be erected on the site will cost approximately $300,000 and embrace eighteen buildings, built in Spanish mission style with an imposing façade on Washington Boulevard.” In June 1918 Culver formally announced that Ince would spend a somewhat scaled- down but still impressive $200,000 on the property. And yet a month later, on July 19, 1918, when it was reported that Ince had formally acquired the property on an “option basis”; this time the $132,000 was listed as a “loan” from Culver, which, in this case, was rather accurate.

Immediately Ince made it clear that this studio, whatever its method of conception, was to be something special. He kept, somewhat surprisingly, the idea of that “imposing façade” on Washington Boulevard. And he, and his architects, spent an unusual amount of time planning the aesthetics of the studio, and the aesthetics that could be achieved by filming at that studio. For example, in December of that year, Ince’s publicists announced to the trades that “the studios are situated on the main boulevard running from Los Angeles to Venice of America. So on the one side is the big city, on the other the ocean and to the rear is an imposing range of mountains. Picture atmosphere of every quality is conveniently available.”

In his supervision of the design of his new plant, Ince obviously tried to avoid the pitfalls of life in Inceville, with its muddy streets, roaming Indians, and wrong-side-of-the tracks ambiance. To this end it was announced in July, as if to prove that the movies had finally grown up, that “architecturally, it is intended that the new studios will be especially attractive.”

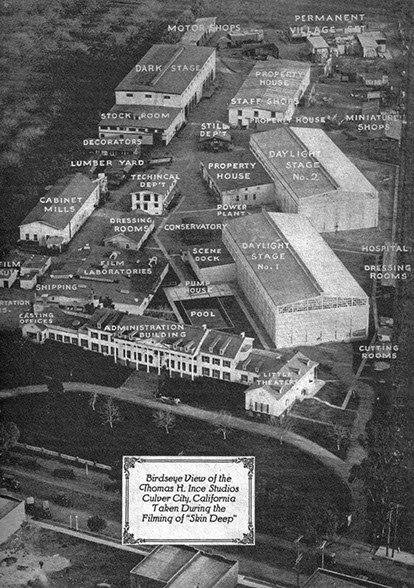

Ince also wisely configured departments that worked in proximity to one another in the same geographic area on the lot, so as to “minimize motion in handling scenery and players,” as Ince’s biographer would later describe it. In addition to the usual studio departments, he included a general store, a hospital, and even a weather bureau to predict days when shooting outside would be impractical. He built a film lab which, unheard of at the time, could create release prints as well as the “dailies” used for film evaluation and editing during production.

The original plans called for two glass shooting stages, each 72 by 180 feet, although plans for a third one, the same size, were added soon thereafter. A backlot which was literally at the back edge of the property was also included. A 1922 article on the studio gives us one of the few written descriptions of this part of the plant during this time, stating “a number of permanent sets have been constructed on the lot, such as village street, fronts of buildings, the front and side elevations of fashionable homes and cottages of humble peasants. These sets can be dressed to fit the particular picture for which they are used, but the main parts of the structures are left intact, minor changes only being made.” This proto-backlot soon gave way to the more long- lasting second property across from the main lot.

The most striking feature of the studio was, as had been planned from the beginning, its administration building, a two- story structure with ornate, and in hindsight somewhat ironic, plantation- style columns. The building, known then and now as the Mansion, resembles George Washington’s Mount Vernon when viewed across the lawn from the street, which, of course, is most significantly named Washington Boulevard.

An early architectural concept drawing for Ince’s third studio. Except for the cameraman cranking away on the left the property could be a Virginia equestrian site. (1918)

The Mansion, along with the rest of the studio, was designed in 1919 by the Milwaukee Building Company’s Gabriel S. Meyer and Philip W. Holler, who in 1927 would design Hollywood’s world- famous Grauman’s Chinese Theater (where the premiere attraction would be The King of Kings [PDC 1927], shot on the Ince lot!). The Mansion is sometimes identified as being built as a set for Ince’s Barbara Frietchie (PDC 1924), although a look at the date for that production proves that the building was requisitioned, not created, for that Civil War–set production.

Ince’s office, inside on the second floor, was adjacent to an elaborate dining room which was designed with a nautical flair, resembling, again somewhat ironically, a ship’s cabin which looked like the interior of his beloved yacht, the Edris. His love of the water was also reflected in a swimming pool, actually a studio tank, in back of the building—which gave the lot an almost jaunty, colonial revival / country club feeling, which was most incongruous indeed during this whirling makeshift era when most of his competitors’ lots looked more like Inceville than Mount Vernon.

Harry Culver, obviously, was delighted to have Ince back. He showed his appreciation by throwing an elaborate party on January 4, 1919, which include a ceremonial “key to the city” presentation and an appearance by local balloonist Al Wilson, who wrote Ince’s name in smoke above the studio.

Ince would run that studio from 1919 to 1924, continually reviving and streamlining both his production process and his production facility during his entire tenure, adding stages and sets and departments as well as genteel tree- lined sidewalks and landscaping between buildings, even as he added to his film library. He also, undoubtedly, made Harry Culver very happy when the King and Queen of Belgium, along with Prince Leopold, toured the studio in 1919, the first ever visit by royalty to Culver City.

1918 studio plot plan

A 1922 aerial photograph of the lot and a promotional adaption of that photograph, most helpfully captioned with the assorted departments at work there during that era.

But Hollywood, or in this case Culver City, was changing in the 1920s. In hindsight, which is always the best way to view the rumblings of history, it is apparent that the very system that Ince had largely invented and streamlined eventually would have destroyed him as well. As an independent producer, even one with his own studio, Ince was, to a large degree, dependent on the majors for financing, talent, and distribution. By this time, he had moved into producing big- budget, prestige films like Anna Christie (Associated First National Pictures 1923), based on Eugene O’Neill’s play, an interesting contrast to the costume- stealing Indians he had featured less than a decade earlier.

Like later independent producers such as Cecil B. DeMille and David O. Selznick, both of whom would inherit Ince’s studio, Ince tried during this period to make fewer but better movies than the majors were able to create on their assembly lines—even though those assembly lines had been made possible through his innovations at Inceville and Culver City. But less product meant less profits for the producer, and so during these later years Ince often rented his studio’s stages and sets to other independent productions, usually at a loss.

In 1919 Ince founded a company named Associated Producers with some other independents, but it was ultimately absorbed in 1921, somewhat ironically, by First National, which had been created with the same goals. Also, in 1921 he formed the Cinematic Finance Corporation, an attempt to secure financing for quality films produced independently. It too was ultimately unsuccessful.

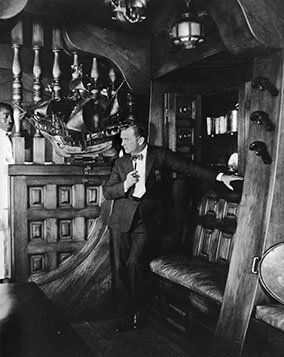

Thomas Ince in his “ship’s cabin” dining room, circa 1924, and the same location as it looked in 2013.

In 1924 publisher- producer William Randolph Hearst entered into negotiations with Ince about using his studio as a base for his Cosmopolitan Productions. Cosmopolitan, like Ince, was an independent production company, but unlike Ince, it was exceedingly well financed, due to millionaire Hearst’s personal involvement with star Marion Davies.

In November 1924, Ince boarded Hearst’s yacht, the Oneida. Other guests on board that lost weekend included actors Davies, Charlie Chaplin, Margaret Livingston, and Jacqueline Logan; writers Elinor Glyn and (allegedly) Louella Parsons; Russian dancer Theodore Kosloff; and other Agatha Christie–style characters. At some point during the trip, Ince became ill and was rushed home, where he died at the age of forty- four of apparent heart failure.

Immediately, spurious rumors began circulating that Ince had been shot by Hearst, mistaking him for Chaplin after Chaplin had been caught in a dalliance with Davies. These rumors are apparently completely unfounded, and many authors and researchers and detectives have filled hundreds of pages of footnoted copy debunking them. Yet these same rumors, fanned by movies and books and speculation, have continued and have kept Ince’s name alive and on the fringes of the public’s interest long after his films and his innovations and his unfinished life have been, sadly, completely forgotten.

Today, all of the principals in this drama, even those possibly apocryphal Indians, have long paddled upstream into the dark compost of history. Ince too is gone, of course, like the letters of his name written in smoke on that long- ago opening day. Yet his studio—two of his three studios, in fact—survives today.

And in one of them is our story.

In the 1920s Ince rented his studio facilities out to other producers, a practice later owners of the lot would continue. (1924)

The original Ince backlot was in constant flux due to the very limited real estate available for standing sets. The second photo is from Barbara Frietchie (1924); the others have not been identified.

Thomas Ince promotional emblem. (1920)

To read more about the Ince Studio and the life of Thomas Ince

you can purchase a copy by clicking on this link in blue: