COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, and the five stages of Los Angeles

One day, while working in Chicago, Frank Lloyd Wright got a phone call that would alter his life. It was a voice on the telephone letting him know that “Mamah” Borthwick, his muse and the love of his life, and all her children were murdered. On top of this, Wright was told Taliesin, his studio and the home he built for them in Wisconsin was burned to the ground. Meaning, in the space of a few words, faceless words levied cold by some well-intended Pheidippides — life as Wright knew it ceased to exist.

And there was nothing he could do about it.

In cases like this, escaping inside or outside yourself is a natural response, and for artists, especially ones who see things and feel things more deeply, their flight can manifest itself in their art.

As such, with his hearth broken and his heart slaughtered, Frank Lloyd Wright left the rural Midwest and took a commission in Tokyo, Japan. There, he built the massive Imperial Hotel. After, Wright would abandon the Midwest altogether and do what many have done when life has placed them somewhere they didn’t want to be, Wright moved to Los Angeles, a place Wright would later describe (with a smack of angular disdain) as "that far corner of the United States." I love Wright's descriptive because of where Wright chooses to place Los Angeles metaphorically and geographically, like it was an anomalous detail in one of the exteriors of his buildings. "Over there"... in "some other place" where people and the way they behave bears no connection to the whole, and where having congress with anyone but yourself is an unthinkable idea. So, lets draft Los Angeles as it is, and lend like a pencil gliding on vellum a unique weight to every word — That. Far. Corner.

Wright first visited Los Angeles in January 1915, less than six months after the tragedy at Taliesin, and he would move there full time in early 1923. Still reeling from the loss of his home and family, Wright would within this time frame build five houses in LA that are linked by their concrete uniqueness and their ironic inability to be a home fit for anyone or anyone's family.

As a set of five, these five houses are different from the rest of Wright's body of work.

They're harsh. Opaqued in one color. Crypt-like and Cold. Each stand like a fortress, with fists clenched and trembling, erupting from the spot where Frank Lloyd Wright anchored them. And, writer/director Christopher Hawthorne describes them as such in his insightful, well-written documentary for Artbound: That Far Corner.

Hawthorne's documentary is easy to watch, and it's unafraid to connect the dots between where Wright was in his life before and after the tragedy at Taliesin - and how the tragedy could have affected the architecture Wright created in the years after its wake. To do this, Hawthorne takes his audience back to Oak Park, Illinois, to a time before circumstances derailed Wright and in a gentle way, Christopher Hawthorne delivers his audience to an epitaph carved so unexpectedly into the conclusion of his documentary that it's hard not to be moved by how Wright used his time in Los Angeles as catharsis.

But I have one further observation that I would like to lend. One the author of the documentary seems to glide just above from saying, and that is that Frank Lloyd Wright’s five LA houses seem to manifest what many would call "the five stages of grief." Even if the homes themselves as a set of five do not follow the five stages in a linear way as they are typically described: Shock [1], Denial, Anger, Depression and Acceptance, it's hard not to see each stage of grief within the emotional arch of each of these buildings.

As anyone who has come home to learn that a front page news story has cut a hole into their life knows, the stages of grief morph and twist organically, and that you shift through all five stages at the same time while you predominantly rest within one of these five overtones.

For that reason, and by way of using the concept that life lends to us circumstance, and that no matter how hard we try to push circumstances away, they can bleed into our lives — coloring almost everything we do. As such, by way of using the five stages as a general idea, please view Wright's five LA houses by applying this filter as a backdrop. I think if you do, the feeling erupting from each of the homes Frank Lloyd Wright built in Los Angeles will make perfect sense:

The Hollyhock House - DENIAL

The Millard House - DEPRESSION

The Storer House - ANGER

The Ennis House - SHOCK (or Horror)

The Freeman House - ACCEPTANCE

If you haven't seen the Artbound documentary That Far Corner by Christopher Hawthorne, I think you will find watching it is well worth of your time. The documentary does a great job showing off the nests Wright built in LA and how each were like catalysts that allowed Wright and the tragedy that befell him to take flight.

Screenshots from That Far Corner are by permission of JP Shields, publicist of KCET

All Images courtesy of KCET/Artbound, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The author would like to thank JP Shields for his support and Christopher Hawthrone for what was a rather insightful look into five concrete houses Wright built in Los Angeles.

This article is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

Note [1]:

I adapted the Elisabeth Kübler-Ross model for "the five stages of grief" by removing "Bargaining" and replaced it with "Shock." The reason for this is that her five stages are based on someone recovering from loss from a death due to a terminal illness. Experiencing horrific loss by way of an ax murderer abruptly killing your family, and burning down your home and the office you designed is something else. Anyone who has experienced horrific loss will tell you that "Bargaining" by way of the "If I did this... or that..." is a part of it. But it is not as big a part of it as the epic echoes of post traumatic stress one experiences from a loss this severe. For that reason, "Bargaining" was discarded and replaced with "Shock," a much more prevalent part of this type of recovery.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

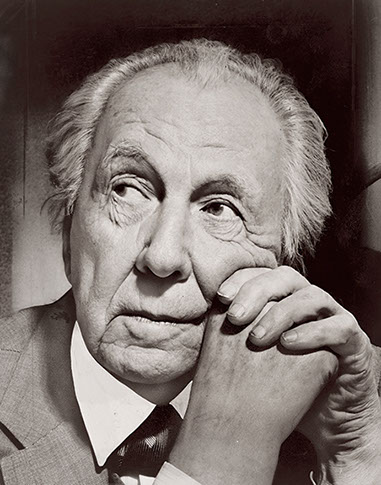

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1954, image courtesy of KCET

Frank Lloyd Wright, and the five stages of Los Angeles

© 2018 Ron Barbagallo

The Freeman House

ACCEPTANCE

The Storer House

ANGER

The Hollyhock House

DENIAL

Unfinished in its own way (like the first of Wright's LA houses: the abandoned Hollyhock House project) or maybe simply economic in how modestly it is detailed, the Freeman house is Wright's final effort in LA during this time period. Encased in one color like the four concrete homes that proceeded it, the Freeman house is the only one of these houses that pokes large holes into its nest by way of its many oversized windows. These bursts of light feel like release, like Wright created an escape plan waiting for a bird to take flight. Another rather poetic detail of the Freeman house is the image of a rose. Roses are cut into and embedded repetitiously into many of this home's concrete blocks. More a reflection of the love of the Freemans shared, it's hard not to see this single rose as a goodbye gesture left by a loved one, not unlike a rose one might leave on a tombstone, or in this case, one left pressed into a concrete block.

Square-jawed, with five gridded teeth in the center of its facade, the Storer House looks at you like it was a Jack-o'-Lantern staring down from Hollywood Boulevard. It is the third of Wright's LA homes and the one that feels the most stern. Humorless and rigid in a way that exudes in every hard line used to form its skin, the living room of the Storer House was described by one resident of the house as "a drama of Sophocles." While Wright himself, as the house neared construction, referred to the home as "a tragedy" and said it was "lacking joy."

The full effect of tragedy takes years to seep in. Like a virus that sweeps over us, we hold on to who we were before we were infected by loss and cling to what we were doing before the phases of grief redirect us from who we were — to who we will be. As such, the Hollyhock House manages to all but deny what happened at Taliesin. Its design holds on to many of the warm, celebratory aesthetics that defined Wright's work before the loss of his family. Capable of singing the body electric in ways the next homes Wright would build in LA do not, the Hollyhock House is a concrete temple, and one whose outer shell contains a recessed quality. That need to artistically hold oneself tight foreshadows what one will see in the next four homes Wright will build here in the city of angels.

The Ennis House

SHOCK

Best known to the world by way its appearances in movies, television, and video games, the Ennis House is the largest and fourth of Wright's LA houses. A punishing procession of endless corridors and antechambers, the Ennis House has within it the flavor of an Escher etching, lending to the person who enters its monochromatic maze the nightmarish idea that no matter where you go, you in fact end up nowhere.

The Millard House

DEPRESSION

Holding the world at arm's length, the Millard House pokes its nose out of the cave-like spot where Frank Lloyd Wright placed it. Hiding in the shade, all alone, the second home Wright built in LA takes a contemplative stance. As if it needed to push the world back so it could fully consider the immediacy of its surroundings, and that needing to do that was by itself a life saving act. In this way, the Millard House is reminiscent of what happens when one pauses after a tragedy, trying to anchor oneself from falling into a fog of depression and wondering why something so heavy could have happened.