COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

An influential yet often overlooked part of the history of animation art collecting involves the inventive contributions of Disney cel inker and painter Helen Nerbovig. It was Helen’s clever use of discarded production cel paintings and her airbrushed backgrounds which came to be known throughout the animation art world as “Courvoisier cel setups and Courvoisier backgrounds.”

The youngest of 3 daughters, Helen Gertrude Nerbovig was born on August 21st, 1915, in a hospital owned by her maternal grandfather located in pastoral Sheldon, Iowa. Helen’s father Halvor, a man of Norwegian decent, worked as a jeweler and watchmaker who traveled extensively for business. He moved his family to Minneapolis when Helen was approximately 3 years old. Helen’s mother Georgiana, surprised her husband on one of his business trips to Los Angeles and on a flip of

a coin made the decision to relocate the family to the warmer climates of California.

The Nerbovig’s drove cross country in 1924 and eventually settled in Los Angeles where Helen and her older sister Buf E. entered the local school system. In the era of Art Deco and Art Nouveau the Nerbovig sisters studied drawing and composition one Summer at the Otis Art Institute located on the edge of Mac Arthur Park. Helen’s artistic abilities were already evident when as a senior in high school she entered a citywide poster competition and won. Her artwork was published that following year on the poster and program cover for the 1935 Easter Sunrise Service at the Hollywood Bowl. Helen graduated Hollywood High School on June 19th, 1934.

During the Great Depression Helen worked at a variety of art related jobs which included packaging lipsticks for a cosmetician out on Gardner Junction. She was quick to fill out an application when she heard the nearby Disney Studio was training girls to “ink and paint” on their first feature Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs. However since the seven month training period offered at Disney was without compensation Helen, whose family relied on her salary, sent her sister Buf to train instead. Later, Helen worked out an arrangement where she trained at Disney at night. The need for inkers and painters became so great that the Disney Studio started to pay trainees a salary of a dollar a day. With this, Helen was able to leave her day job and became the one of the first paid Disney trainees.

Helen Nerbovig painting 3-dimensional models for Joe Grant's department at Disney.

Image courtesy of the Nerbovig family.

DISCOVERING HELEN NERBOVIG

Both Helen and Buf successfully graduated from the Disney training program and, according to official Disney records, were hired full time on May 2nd, 1938. Helen skillfully fit into the Ink & Paint department earning a starting salary of 16 dollars a week painting cels for short subjects and features. As a hobby, she made greeting cards for friends by taking cels left after production and assembling them against backgrounds she created using airbrush and decorative papers. It was not long before one of Helen’s cel setups caught the eye of Walt Disney.

Buf E. Nerbovig recalls “At the end of Snow White they were getting the stuff ready for the morgue (a place at Disney used) to hold scenes and backgrounds... that’s when Helen put together a beautiful (cel) setup to give to Walt for his office. We used to go back and forth and take watches home. Walt collected music boxes and he used to send them home because my Dad, he repaired these things.”

Helen’s cel setup so impressed Walt that he later had her prepare similar setups as VIP gifts from the Disney Studio. When San Francisco art dealer Guthrie Sayle Courvoisier formally approached the Disney brothers in the summer of 1938, Walt did not have to look far to think of someone to run a new department devoted to the design, preparation and assembly of Disney production art for Courvoisier to distribute.

The “Cel Setup Department,” as it was called, at Disney was headed by Helen Nerbovig. Here Helen selected a consecutive sequence of choice cels and designed a representative background to accompany them when a production background was no longer available. This initial setup was used as a prototype to mass produce identical backgrounds to complete the remaining cels from the sequence. At its peak, 20 young women helped Helen execute her designs by using registered stencils to create airbrushed backgrounds for these setups. Some cels were trimmed to the outline of the character and adhered to backgrounds while others remained full sheets or slightly trimmed sheets which on occasion were adhered to a background. A coating was often added to the reverse side of the paint layer. Dramatic shadowing effects were sprayed with airbrush uniting the newly prepared cels to Helen’s backgrounds.

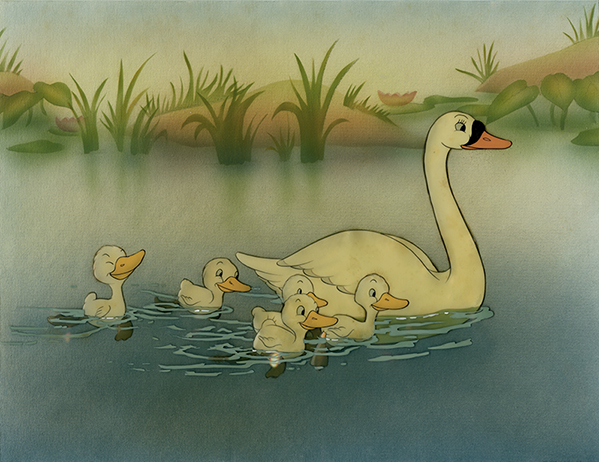

Water effects production cel, and cels trimmed to their outline adhered to an airbrushed Nerbovig stencil background. These effective paper backgrounds are typical of the backgrounds Nerbovig had her staff make. Simplistic in their execution, backgrounds like this complete the image and create an environment for the setup.

After their wedding Helen continued her work in the Cel Setup Department, taking maternity leave when daughter Jorjana was born on October 20th, 1942. Upon returning to Disney, Helen worked on other projects which included painting color models, figurines and puppets in the Character Model Department run by Joe Grant. She also worked as a Checker on Disney’s 1943 feature film Victory through Air Power. Later in the Publicity Department, under Roy O. Disney, Helen inked and painted pages drawn by Hank Porter which appeared in Good Housekeeping Magazine and painted the finished cover art for Deems Taylor’s book on Fantasia. Whenever needed Helen still created cel setups for Walt until resigning from the company on October 28th, 1949 to work at home inking comic art and to be with her child.

In her golden years, Helen looked back on her work with pride. “When you got into working on Snow White,” Helen reflected in an interview held in 1990, it had a personality and a charm about it... you knew you were creating something that was going to last. I really felt that way.” By 1990 the cel setups she worked on in her youth had become a mainstay of the New York auction scene and grew to take a prominent position in the finest collections of animation art.

Helen Nerbovig McIntosh died at age of 76 on April 11th, 1992. Unlike the animation art computer rendered in this modern age, Helen had a personal role in the creation of Disney animation art from that classic period. She hand inked and hand painted some of the production cels she later assembled into cel setups. And it is in her work, like any artist, she can be found - between the layers of translucent airbrush, in her imaginative design solutions and in her backgrounds. Here, the educated art collector will continue to discover Helen Nerbovig.

© 1997 Ron Barbagallo

Helen added variety to the art she produced for Courvoisier by incorporating printed papers and wood veneer she purchased from McManus and Morgan on 7th Street in LA. Colored papers with small silver stars, polka dots and checked patterns were used to create smaller simplified character momentos for display in children’s rooms. Helen also painted backgrounds on actual wood veneer panels because the wood grain reminded her of the interior of the Dwarfs’ cottage. These wood veneer pieces were sometimes quite elaborate and could contain hand painted shadow effects, hand lettering and/or interior elements. Wood veneer treatments were not exclusive to artwork from Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs (1937) but also included production art from Pinocchio (1940) and Brave Little Tailor (1938).

In the Spring of 1940 Helen met her Prince in the form of oil painter Robert McIntosh. Although he had been working for nearly a year in the Disney multi-plane department under Dick Anthony, the couple first met while attending a ballet at the old Philharmonic Building and began their fifty two year marriage on July 15th, 1940. Like a lot of Americans during World War Two, the artists at Disney worked a five and a half day week. Robert McIntosh remembers “I was working on a scene, a multi-plane scene for Rite of Spring and it was something involving the footprints of the dinosaurs in the wet clay and I remember painting that and then I laid my brush down and then went home and showered and shaved and got into my new clothes and went and got married.”

Images are © Disney Enterprises Inc.

The author would like to thank Sarah Baisley for giving me a platform to create without micromanaging me in any way, and the Nerbovig family: her husband Bob, her sister Buf. E, and daughter Jorjana for treating me like family. Images from The Research Library at Animation Art Conservation.

This article is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

A cel setup from Walt Disney’s 1937 feature film Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs.

Four production cels were carefully trimmed to their outline and adhered to an airbrushed presentation background indicative of Helen Nerbovig’s airbrush and Art Nouveau styled work.

The use of wood veneer purchased at McManus and Morgan on 7th Street in LA was a signature element to the backgrounds Helen Nerbovig had the women who worked in her department make for the cels she prepared for Courvoisier to distribute.

Helen created an entire line of character momentos from Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs for the Courvoisier Galleries to distribute. Cel paintings were displayed against wood veneer (as seen one image up top) or on decorative paper backgrounds (as seen here). Dramatic airbrushed shadowing effects were often added to unify the cel painting to these backgrounds.

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO: