COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

Over the course of his 89 years, Chuck Jones has seen animation grow from its beginnings through the heyday of the 1930s, ’40s and ‘50s, past its depths in the 1970s, and onto the renaissance in the 1990s. During that time, Jones has worked in nearly every capacity in the art form, leaving behind a body of work as a director of animation that boasts the only two Warner Bros. shorts included in the National Film Registry.

I first met Chuck Jones in 1996. Later that year and on November 8th, 1999, I took the opportunity to interview him. Our conversations revolved around history and on the art and philosophy of animation.

Condensed from these two interviews and reworked by Chuck Jones and myself,

"CHUCK JONES, in his own words," was molded to reveal the reflections and insight of animation director and eight time Academy Award® nominee - Chuck Jones.

Another filmmaker who put humanistic qualities and mannerisms in his performances was Charlie Chaplin. When you were younger, you lived near where Chaplin worked?

CHUCK JONES:

His studio was two blocks from us, at La Brea Avenue and Sunset Boulevard. Because there was no sound, they shot the films outside. As kids, we could go there and look through the fence and watch him work. He was kind of a hero to us, and we loved his films.

When we watched them in the theaters, it never occurred to us that anything was done over and over. When we watched them shoot, we discovered how difficult it was to get it just right.

My father saw Chaplin do one scene 62 times before he got it the way he wanted it. Well, I don’t have to pretend to do anything like that. On many occasions, I have drawn over 50 drawings to get one right.

Let's talk about some of your colleagues from the early days. A good place to start would be when you left high school at 15 and went to the Chouinard Art Institute. You graduated during the depression. What type of work were you able to find?

CHUCK JONES:

I tried to get work at a commercial studio, but couldn’t letter professionally. Unless you could letter professionally, you might as well forget it. Fred Kopietz, who had been in art school with me, called and said he was working at Ub Iwerks’ studio on Western Avenue and wondered if I wanted to come to work there.

I couldn’t believe I might get paid to draw. I was right. They didn’t want to pay me to draw. In 1931, they hired me as a cel washer and then as a cel painter, a cel inker, and eventually, an in-betweener. I wasn’t a particularly good in-betweener.

That was the time when Shamus Culhane and Bernie Wolf and Grim Natwick were working there. They had all come out from New York, where they had been working.

When I was hired, it seemed to me that Ub was an old man. However, he was an old man in the animation business. I was about 18 then, and he was 38. He was ten years older than Walt Disney and Carl Stalling. It’s hard to imagine how young everybody was.

At that early age, what films were you and Grim Natwick working on for Ub Iwerks? Flip The Frog?

CHUCK JONES:

Yes, and on Willie Whopper and a couple of other horrible things. Ub was a brilliant animator, but didn’t seem to have much of a sense of humor. Walt Disney, on the other hand, probably had the most acute knowledge of humor around in animation. He knew when it was good and when it wasn’t. He was the one who made the whole thing work. Ub was a technician in terms of being a great animator. So, Ub's studio didn’t go very far.

How did you go from working for Ub Iwerks to working at Warner Bros., where you helped redefine the way characters behaved and the way comedy was portrayed in cartoons?

CHUCK JONES:

I don’t know if I can take credit for that, but I can say I needed a job. I had tried working at Charles Mintz’s studio, where they were doing Oswald, The Lucky Rabbit, then gone back to Iwerks.

About that time, Leon decided to start his own studio and he hired a couple of directors from Disney.

Was Bobe Cannon [who would go on to direct UPA’s Academy Award® winning short Gerald McBoing Boing] directing when you started?

CHUCK JONES:

Oh, heavens, no. Bobe, Bob Clampett and I were just in-betweeners. The term, animation assistant wasn’t used then. There were animators and in-betweeners, and that was it. They may have been called assistants at Disney, but not at Schlesinger’s studio. There were also no clean-up artists. Each animator did his own clean up. In fact, there were several animators who didn’t have to clean up their drawings at all because they animated clean. Bill Nolan. Ub Iwerks and Benny Washam were like that. Their finished extremes were always finished.

One of the most interesting things about Warner Bros. in the late thirties onto through the fifties is that whether through lack of corporate planning, or the benevolence of being left alone to experiment - the directors at Warner Bros. each imbued the evolving cast of Looney Tunes’ characters with their own individual personality and unique vision.

In a lot of respects, the approach taken by the Looney Tunes directors more closely parallels that taken by live action directors, like Kubrick or Scorsese when they are redefining an accepted film genre, like science fiction or the gangster picture. The manner of storytelling is reflective of the personality of the director.

How did this step forward take place at Warner Bros.? Was it when Tex Avery arrived?

CHUCK JONES:

The man who was really the leader was Friz Freleng, I think. He was an extremely competent, talented and able director. When Friz came over, he really saved the studio.

Tex had been an animator at Universal and when he came over to Schlesinger’s, he had it in his mind to be a director. Tex told Leon Schlesinger that he had been directing pictures at Universal. Leon never checked, so he hired him as a director. Tex may have helped direct at Universal, but Walt Lantz [creator of Woody Woodpecker and Chilly Willy] didn’t credit anyone but himself, like Disney.

Tex was in charge of one unit. Friz Freleng was in charge of another unit and Frank Tashlin had the third unit. Each unit turned out ten cartoons a year, each almost 540 feet, give or take ten feet.

Originally, there were four animators, a director, a layout man and a background man in each unit. Each unit would work on a picture for five weeks and then start another one. At the end of five weeks, the picture would go to ink and paint and then to camera.

No one was criticizing or lashing out at anyone. No one set themselves up as better judges of our work than we were.

For me, the most important person at Schlesinger’s studio was Friz Freleng. Tex Avery was great, but he wasn’t there very long when we were making Bugs Bunny cartoons. He only made about three, maybe four and then Bob Clampett took over when Tex went to MGM. Personally, I think Tex’s best pictures were made at MGM.

He didn’t have the time to develop the Looney Tunes characters. I am not downgrading him, because he was one of the great innovators - he stretched a gag to its limits. He’d play with film within film. He had guys running right through the screen. I think he was one of the geniuses of animation. He was a vital and necessary force in animation.

People try to imitate that absolute nuttiness, that Tex had, and most of them miss the boat completely. You see his influence all over. Did you see The Mask with Jim Carrey? That was practically pure Tex Avery; very funny.

Tex never knew how good he was. He was a very sad and hurting person when he died. When Tex was dying, I remember, he was in the hospital watching the baseball game with another animator. He said to his friend, “I don’t know where animators go when they die, but I guess there must be a lot of them.” Then, he thought for a moment, and said, “they could probably use a good director though.” Those are pretty much his last words.

Background art is a subtle, and at times, undervalued element in animation. If a background artist, such as your colleague Maurice Noble, do their job correctly, you are not supposed to notice them. They set a stage and a mood for animation to fall upon. At times, they can transcend and lift the animation to another place. I think Maurice Noble’s backgrounds are a good example of this.

CHUCK JONES:

Absolutely. Maurice is brilliant. In most of our films, Maurice would do all the scene layouts and art direction, while I was doing the direction, layout drawings and writing the dialogue. We didn’t interrupt each other. The understanding we had was that we were both enhancing the storyline. He was and is wonderful. The best I have ever worked with.

And you worked with him for a long time?

CHUCK JONES:

I think it was shortly after World War II that Maurice joined my unit. Mike Maltese, the great writer and gagman, came to me about that time, too.

Could you talk a little about Michael Maltese?

CHUCK JONES:

He was a brilliant writer. He and I worked extremely well together. Mike was a great storyman, and we came up with some great stories together. He didn’t write the dialogue; I did that as I did the layout drawings. We didn’t have a script until after I had done all the layout drawings. Mike was a vital factor. Mel Blanc was, too, but Mel didn’t originate characters or write dialogue. He was a great, great actor. We would tell him what we wanted to hear and he took direction brilliantly. The dialogue was written before we recorded it, though. It wasn’t open for change at the recording session.

You also worked with Shamus Culhane, the legendary animator who imbued so much individual personality into each dwarf marching along the mountain crests in the Heigh Ho sequence from Disney’s Snow White And the Seven Dwarfs. What was it like working with him?

CHUCK JONES:

Shamus Culhane didn’t work with me very long. He had a work habit that drove everybody crazy. He’d come get a sequence from me that would run maybe a 75 or 100 feet, take it back to his desk and just stare at it for three or four days, not drawing anything. Then, he would come up an idea about how it worked. When he started animating, and he could animate 50 feet a week. He worked it all out in his head before he began, carefully thinking and analyzing the whole sequence before he ever started to draw.

Did you or your colleagues have any idea that your films would have the long range popularity or influence that they’ve had?

CHUCK JONES:

God, no. We never were conscious that we were doing anything that had any lasting quality. It’s a great surprise, as I am sure it was to Mark Twain, William Shakespeare and so many others. You know, the Globe theater owned Shakespeare’s plays. Talk about history repeating itself. Warner Bros. owns all the characters we developed, and we don’t get any residuals. Not that I’m a Shakespeare, but just to make the point, he didn’t get any residuals either. Shakespeare continued to do what he did because it was his life - he had to do it. I feel that way, too. It never stopped me from continuing to draw. The saddest thing in the world is to find some artist who just stops drawing.

Will you direct again?

CHUCK JONES:

I doubt it. After all, I’m 87. I’ll continue to draw and write. If something comes along I just can’t refuse, I’ll do it if I have time.

Recently, there has been an explosion in animation. Inspired by the strength of Howard Ashman’s storytelling on Disney’s The Little Mermaid and Beauty And The Beast and by the formulaic, but lucrative The Lion King. It's caused existing studios and those not associated with feature animation to jump on the cartoon bandwagon trying to recapture Simba’s profits.

With raised expectations, the animation industry has entered a new phase where the studios focus less on storytelling and more on merchandising films into video games, happy meals and licensed toys. Direct to video sequels and television series are planned before a feature film has even been released.

In the midst of all this commercialism, a lot of films have come out. What over the past decade have you liked and what have you disliked and why?

CHUCK JONES:

Well, I don’t know where it’s going. As I mentioned I recently saw Toy Story 2, and I wrote John Lasseter [the director of the Pixar/Disney film] to tell him how much I loved it. There is hope when films like that are being made.

I surely hope the art form persists. A lot of what is happening now reminds me a great deal of what happened in New York stage in the late 1930’s. Many people in the legitimate theater were so intrigued with stage craft that they believed it was more important than the play itself. The result was that set designers, like Norman Bellgeddes, were given more credit than they deserved. They started doing enormous sets and overwhelming everything. It got to a point where Bellgeddes and Bill Sedfork built a set for Medea, or one of those plays, that extended the stage out over the first 20 rows of the orchestra, and the people in the balcony couldn’t see what was happening. It was ridiculous. They forgot what they were doing.

Along about that time, Our Town was staged. No stage craft at all. It was such a relief. It allowed the audience to imagine everything, which was great. And, that’s true for great cartoons as well. Backgrounds aren’t the dominate factor; they are there solely to support the characters and the story. Like I said about Maurice, we were doing the same job, - enhancing the storyline.

Most of the people who are doing computer animation today have gone overboard. The backgrounds are so enormous and wonderful and beautiful, that you thought you were seeing something better than you were. They’ve gotten so enthralled with the technology and what it can do that they’ve forgotten, or never knew, what they’re supposed to be doing - telling a story and introducing audiences to real characters. The characters have no warmth, not humanity. As Tallulah Bankhead once said, “There’s less here than meets the eye.”

Why do they want to make it more realistic? I mean, Bugs Bunny doesn’t look anything like a rabbit and Daffy doesn’t look anything like a duck. They’re not realistic, they’re believable. That’s the key.

In some of the new huge films, it seems to me that they are showing off instead of entertaining. It’s using a tool just because it’s there.

When Walt Disney needed an opening for Pinocchio, they invented the multi-plane camera, and it worked. But they didn’t invent the multi-plane camera and then use it for everything.

The question becomes, is animation an art form or isn’t it? If it is, I would like to see more people respecting it as an art form. I believe the artist and the art still exist. I believe that the artist, and the art still exists - that you can take a sheet of paper, and a bunch of drawings, and bring something to life. Too many people are overlooking the essence of animation. It is bringing something to life, with the simplest tools. They show off with tools they don’t know how to use and miss the point completely.

When Alexander Woollcott first saw, Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs It was in pencil test. And he didn’t know anything about animation, but he looked at this thing and he said, “it’ll never be any better than it is now.” And it’s true. In the final analysis, all of us are in business because the thing that you’re going to see is always the animator’s work.

The essence of any great animation is the animator’s work. A director can guide and inspire the animator, but you can’t substitute for what the animator must do. It’s the same principle that exists in acting - a moving picture of a photograph is not the same as an actor acting.

When Tex Avery was dying...

he was in the hospital watching

the baseball game with another animator.

He said to his friend, “I don’t know where animators go when they die, but I guess there must be a lot of them.”

Then, he thought for a moment, and said, “they could probably use a good director though.”

Those are pretty much his last words.

Characters © Warner Bros.

© Turner Entertainment Co.

Chuck Jones reunites Bugs, Sylvester, the Roadrunner, Elmer Fudd, the Coyote, Porky and Petunia Pig, Daffy, Pepe and Yosemite Sam in adept shades of oil paint. This 1999 canvas entitled The Grande Saloon measures 3 by 4 feet and recently sold for $200,000.00.

Jones’ understated sense of humor added charm to the 1967 television adaptation of Dr. Seuss,’ sometimes dark, children’s story How The Grinch Stole Christmas. The Grinch is revisited here by Jones in a recent oil painting.

Characters © Chuck Jones Enterprises

© Susan Einstein

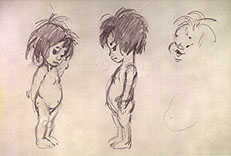

Humanistic qualities like paternal warmth and knowing guidance (Father Wolf), friendly, playful glee (Baloo the bear) and childlike reflection (Mowgli) are on display here, in a suite of four pencil sketches done by Jones as character studies in preparation for Mowgli’s Brothers, a 1976 Jones adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s classic novel The Jungle Book.

© Warner Bros.

© Warner Bros.

Pictured in front of numerous storyboard drawings, Chuck Jones (left) and Michael Maltese (right) are seen holding classical soundtrack recordings which may have served as inspiration for the 1957 Warner Bros. short subject What’s Opera, Doc? This short, which Chuck Jones directed, is one of two animated Warner Bros. short subjects included in the National Film Registry.

Hi Chuck, How are you doing this morning?

CHUCK JONES:

Fine. I am probably in the actuary tables.

Actuary tables?

CHUCK JONES:

According to them, I should be dead. [Jones laughs]

Oh, I don’t think so. For instance, I bet you’re working on something. What are you working on this morning?

CHUCK JONES:

Oh, the older I get, I find myself sketching. I don’t call it work. You do it because you have to. I mean, because I’ve been doing it for so long. Right now, I happen to be sketching a drawing of Daffy Duck as, Uriah Heep [a clerk who continually talks about his humbleness from Charles Dickens’s novel David Copperfield], which is a pretty good role for him.

Maybe it’s the role he was born to play?

CHUCK JONES:

Well, perhaps, though it’s kind of hard to think of Daffy ever calling himself humble.

Chuck, I wanted to start off with some questions about your youth. You were born in 1912 in Spokane, Washington, and relocated to California. Where in California did your family relocate?

CHUCK JONES:

My father moved down here from Spokane when I was about six months old. So, I was only there a very short time. We moved here to southern California. My brother was born in Washington, my two sisters were born in the Panama Canal Zone.

There are many things about my childhood, I don’t remember, of course. I have faint memories, like falling off things. I remember I was once attacked by a rooster when I didn’t have my pants on. That sticks in my memory, but I don’t know where it happened.

Memories of life were more vivid when I was about six. I can remember things happening then because that’s when we moved to our home on Sunset Boulevard, right across from Hollywood High School. My father owned a very nice home there on the first block going west on Highland Avenue. We had an orange and lemon grove; we had that whole block.

Was there was an orange and lemon grove on Highland Avenue and Sunset Boulevard?

CHUCK JONES:

Yes, there weren’t any buildings on that whole block, as I remember it. But I remember that I could walk out and sit on my front porch and watch Mary Pickford ride by, on a white horse as the Honorary Colonel of the 360th Infantry of the Rainbow Division of the United States Army.

I remember going a few different places, including down to Newport Beach, in the summer time.

My brother is still alive and lives in Colorado. He is a very unusual creature, he was a combat photographer during World War II, but he worked in my unit before he went overseas. When he came back, he went into photography and teaching. He’s retired now from a career with UNICEF and a person who can’t get away from the mountains. And I’m a person who can’t get away from the sea.

I read when you were young you were constantly sketching and drawing. Who or what was your inspiration?

CHUCK JONES:

I just wanted to draw. The difference between our family and many others and - teachers, too - was that my mother didn’t judge our work, good or bad. She didn’t criticize what we did, nor did she overpraise it. And, that’s the key isn’t it?

Constant praise is as bad as constant criticism to anybody who wants to draw. If every time I had brought a picture to my mother and she said “That’s wonderful,” and stuck it up on the refrigerator or wall, I’m sure I would have very soon lost respect, both for her and my drawings. After all, I knew, as all children know, that every drawing isn’t wonderful. The result of overpraise, or over-criticism, seems to be that children fail to develop a sense of their own judgment.

People who continue to draw are those who either have the guts to ignore praise and criticism, or are guided by wise parents and teachers.

When you were young, what type of images did you draw? In some way, I want to hear you felt compelled to draw coyotes and roadrunners...

CHUCK JONES:

Well, no. I didn’t draw coyotes and roadrunners. - But, I discovered coyotes, in Mark Twain’s book, Roughing It.

From the time I was very young, I have always read a lot. One of the great fortunes of my youth was that I always had books around me. My father always made it a criteria for every house we rented, that it be furnished and have lots of books. One of the greatest houses was on Mount Washington Drive, in Highland Park, California, where we rented a house owned by Harry Carr, the book editor for The Los Angeles Times.

The house was crammed with prepublication books Carr had accumulated and never thrown away. Books were behind the piano and the basement. Every place in the house, it seemed, was filled with books. My father and mother were both avid readers, but my sisters, brother and I had never seen such a plethora of books, outside a public library before. That’s where I found Mark Twain.

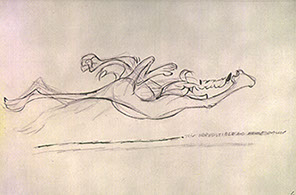

In deliberate and at thought out intervals, a gamut of emotions - some subtle, some extreme - flow from Chuck Jones’ hands, and into each of the four pencil drawings pictured in sequence above and leading into the next page. Through line and posturing, each drawing conveys the personality of the Coyote as he progresses across the frame. An evolving, rounded sense of individual personality is communicated through facial expressions and body language, as each of the four poses moves Wile E. Coyote forward.

The All Purpose Cantor

The Intuitive Recognition Of Potential Danger

The Irresistible And All Out Gallup

The Dramatic Hesitation

What do you like most about Mark Twain’s work?

CHUCK JONES:

The way I found Mark Twain, well, I was just browsing around, I was probably about five or six years old, and I ran across this book, Tom Sawyer. I picked it up, flipped it open to the first page, and saw: “Tom. No answer. Tom. No answer.” I knew right away what was happening.

I proceeded to read everything he had written, with the exception of the two volumes he did on Christian Science. I loved it all. Not many people know that he did that. People don’t know that he wrote A Trap Abroad, one of the greatest books. They know Innocence Abroad, but they don’t know A Trap Abroad, which is the difference between a young man and a more mature man - with a great love of his craft.

I found the Coyote in the fourth chapter of Roughing It, which is a journal he wrote about traveling by stagecoach to Carson City, Nevada. During that period, he kept hold of the things he’d seen and among them were things like tarantulas, and so on. Twain opens that chapter with a description of the coyote, which is about as accurate as anybody has ever described one. He, also, humanized him. And that was kinda news to me. I hadn’t run into anything where I felt that a coyote was like a human being.

He described how the coyote dressed and so on. At the end of the paragraph, Twain wrote, “He may have to go 10 miles for his breakfast and 30 miles for his lunch and 50 miles for his dinner, and we ought to pay attention to that and give him his credit, because he does that instead of laying around home, being a burden on his parents.”

It was a new concept to my young mind, this way of humanizing the coyote’s traits. It’s a concept that stayed with me. Every year I re-read that book [Roughing It], including this year. Each time I re-read it, I find something I don’t expect. Obviously, I wasn’t looking for ideas when I was five or six years old, but I got them anyway. Mark Twain gave me the whole key to thinking that animated characters think the way we do.

Because you must understand, I was born in 1912, two years before Winsor McCay did Gertie The Dinosaur. There was a long dead period after that when animation was just moving comic strips, you might call them, until Steamboat Willie. And, then it came to life again.

By the way, I’d like to reiterate that the term, "animate" as defined by Noah Webster is “to evoke life.” “Evoke life.” And that’s what animation is all about. To some extent, that’s what’s missing in what is currently called animation.

What I am afraid of is, I’ve seen the birth of animation, the growth of animation, and in some way, the decline of animation. I am glad to see films like Toy Story 2. That is wonderful animation, true animation.

We were fortunate in the early days [1930s - 1950s] because nobody at Warner Bros. paid much attention to us. As long as we made the cartoons that could be sold, no one bothered us much. No one ordered us to make anything better, and I don’t think we were making much effort to make things better either. We were experimenting and looking for different ways to evoke like, if that’s not too presumptuous. When Bugs became popular, why they asked us to make some Bugs Bunny’s.

© Warner Bros.

I think people will continue to enjoy the Coyote cartoons we made because he makes the

same kind of errors we do.

We tried to inject character in them...

we were drawing -

CHARACTER,

not drawings.

Drawing is simply a way of getting

it on the screen.

Was there much instruction or involvement from Leon Schlesinger?

CHUCK JONES:

Nothing, zero. I’m certain that’s why we were as successful as we were. Leon Schlesinger owned Pacific Art And Title and created the titles for most of the feature films all over the country. He had a lot of money from that.

He would come back where we worked at Warner Bros. and look around with disdain and say, “This is dirty back here, but on the other hand, many a masterpiece has been made in a garret.” Schlesinger had a pretty pronounced lisp, by the way, and our director Tex Avery, came up with the idea of imitating his speech impediment for Daffy Duck.

Between 1938, when I started, to 1964 or ‘65, when Jack Warner shut the studio down, we made about 30 characters that are known internationally. In addition, we created 45 or 50 other characters known well enough here in the United States to support an enormous licensed product industry. And why was it possible to create so many successful characters? I think it’s because we didn’t have to answer to anybody. It wasn’t until some of the characters became especially popular that we were ordered, or encouraged, to make more pictures about them.

There were three units, each making ten pictures a year. If management wanted six more Bugs Bunny’s, we would just split them up and do two each. That was our decision, not anybody else’s.

You know, I believe the process of success involves stumbling. Winston Churchill once said: “Many people stumble over a good idea. But they get up and brush themselves off, and walk away as though nothing had happened.” We were fortunate. We didn’t do that. We stumbled over some good ideas and didn’t walk away. We were able to continue drawing for it’s own sake.

You know, most people are most comfortable and like Daffy Duck. Why? I think it’s because Daffy makes the same kind of mistakes we all make.

And, I think the Coyote is the same way. I think people will continue to enjoy the Coyote cartoons we made because he makes the same kind of errors we do. We tried to inject character in them, but we didn’t do it consciously.

All of us knew we were drawing - CHARACTER, not drawings. Drawing is simply a way of getting it on the screen.

I think it’s worth noting, that the seven dwarfs [from Disney’s 1937 feature film] were really seven attributes of a human being. They didn’t try to crowd them all into the same character. Yet, if you look carefully, you’ll see the idea of one character who sneezes, one who was sleepy, one who was happy and so on. It is simply an examination of a single person, who is everyone of those things. That’s why we all recognize them.

Recognizable, humanistic qualities inside the drawings?

CHUCK JONES:

Yes, it’s character we can recognize.

Yes, that is what’s lacking, but even more than that, the incentive behind making animation today is not as it was when Walt Disney was making the original Fantasia and Pinocchio.

Artists working at Disney in the post 30’s Depression were classically trained Fine Artists - who in a stronger economy would have been pursuing their own careers. They came to animation with life experience, and an appreciation of art, literature and music. They were not trade-schooled cartoonists or animators retreading old territory.

They also had the benefit of a genuine storyteller in Walt Disney.

Today, studio executives make animation for entirely different reasons.

Their impulse to put commerce before craft has removed the art and the essential need for artistic vision from the process and they've replaced that with meddling executives trying to be artists, artists who need to be compliant first, and line of licensed products.

The motive behind making the animation in the thirties and forties, had more to do with inspiration and passionate storytelling in a medium that was steadily redefining itself.

CHUCK JONES:

Yes, you are right. Animation seems to be downgraded these days. When Fantasia was made in 1940; they were artists. Creativity is the key.

Of all your projects, what are you the most proud of?

CHUCK JONES:

Well, I’m not proud of any of them. The main thing about any creative work, including animation, is you can’t do it the best. You can’t become the president of animation. There’s no such thing as the best piece of animation because someone will come along and do it better.

I'm surprised that the cartoons we made have been around so long and continue to make people laugh. I’m not being excessively modest, it just continues to surprise and delight me.

These days, I’m drawing and painting, in oils and watercolors. I’m doing the characters, life drawings and other things too. I’ve never stopped drawing. I doubt if a day go by that I don’t do a drawing of some kind. Drawing is something that is catching. It’s a wonderful and terrible disease.

I never try to compete with anyone. I don’t even try to compete with myself.

There are two essentials for me.

I try to imbue personality into each character with a simple line.

The other thing is, I have to read everything that I come across. It really doesn’t matter what it is. When I got in the habit of reading at such a young age, I started to develop taste. I didn’t have to be told what was good or bad by others.

The same thing is true in animation and in any other career or interest. The more you know about it, and the more you study it, the more you build your own attitude towards it. Those things are that are the most vital.

When my daughter, Linda, was in junior high school, she was a fan of the book based on Ben Franklin, Ben And Me. When she saw the Disney film Ben And Me [1953] she was incredibly disappointed at the fact that it didn’t have much relation to the book at all.

Later, she discovered that the director of the film, [Hamilton Luske] had not read the book. I feel that way, too. It’s hard to understand how someone can use the title without respecting the author enough to use the story.

The Sword In The Stone [1963] was another example. The book is a great example of our literary heritage, but the film minimized it, bringing it down to a light tale about a witch and a wizard. There was some funny stuff in there, but it had nothing to do with the book.

Because of my strong feelings about his, when we [Chuck Jones Enterprises] set out to do Mowgli’s Brothers from Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, I read it over and over again. We had signs up all over the studio saying, “Rudyard Kipling is the screenwriter of this film.” We did everything we could to stick strictly to the story as Kipling told it. It’s still used extensively in schools all over. After Disney made The Jungle Book [1967] I was unsure about the pronunciation of the lead character’s name, Mowgli. I had always heard it pronounced as if the first syllable rhymed with “cow,” rather than “crow.”

Before we started our film, I discovered that Kipling’s daughter was still alive and called her. In an elegant, British dowager-like voice, she confirmed my pronunciation and added, “and, I hate Walter Disney.” It was the only time I ever heard anybody call him Walter. In her lifetime, she said nobody ever pronounced anything but Mauwgli.

You worked at Disney for a brief time - between July 13 to November 13, 1953, to work on the early stages of Sleeping Beauty [1959]. What brought you there and what did you do there?

CHUCK JONES:

I went to Disney because Jack Warner decided to close our studio. He had brought out a film called House Of Wax, one of the first three dimensional films. It was a novelty, but he seemed to think the future of films was in 3-D, so he closed the studio.

I worked on Sleeping Beauty for a short time, but the conditions were so completely different that I went to Walt and told him there was only one job worth having at Disney, and he had it.

Any closing thoughts?

CHUCK JONES:

I was very fortunate. I have done almost 300 cartoons in my lifetime. I think a lot of them were insufficient. Some of them are really bad, I guess. But I was continually diverted and urged by myself and by the conditions that existed, not by the people that I ever worked for. I had the opportunity to express myself in so many ways.

Nobody could ever convince me, that there is anything more wonderful than being paid for doing what you love to do. I couldn’t have been more fortunate because that is what happened to me.

Character and background layout © Warner Bros.

© Warner Bros.

I believe that the artist, and the art still exists - that you can take a sheet of paper, and a bunch of drawings, and bring something to life.

Too many people are overlooking the essence of animation.

It is bringing

something to life,

with the simplest tools.

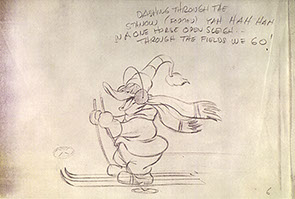

Daffy Duck confidently skies along in this pencil drawing made by Jones for his 1953 Warner Bros. short subject Duck Amuck, the second short by Jones included the National Film Registry.

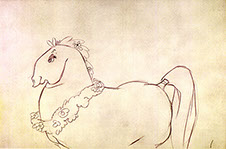

Under Jones’ direction, Maurice Noble created many background layouts which were used as backdrops for Chuck’s character animation. This drawing by Noble was made for the 1953 Warner Bros. short subject Duck Amuck.

Jones’ ability to create lasting characters is apparent even in this early conceptual drawing of Michigan J. Frog, created for the 1955 Warner Bros. short One Froggy Evening. This film is devoid of dialogue. Instead, the main character communicates through manner, expression and song and dance. Although he appeared for a few minutes in this one short, his personality was so memorable, that 40 years later, he reappeared in another short directed by Jones and went on to become the mascot of the WB network.

All art/photography is as indicated above:

© Warner Bros., © Turner Entertainment Co., © Chuck Jones Enterprises, © Susan Einstein, © Ron Barbagallo. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The author would like to thank Chuck Jones, Linda Jones Clough, Craig Kausen, Dean Diaz, Dave Smith, Dina Andre and Amy Genovese for their time, assistance and encouragement in assembling this work.

This article and interview is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

Photographs of Chuck Jones © Ron Barbagallo

<

>

CHUCK JONES, in his own words

the director and the art conservator's cut

© 1996, 1999 / revised 2015 Ron Barbagallo

PART OF the Lost and FOUND series FROM

THE RESEARCH LIBRARY AT ANIMATION ART CONSERVATION

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO: