COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS WEBSITE

Getting back to your career path, you come off of The Iron Giant, and the next project for you is not a film you needed to fix but rather one you wanted to make, right? The Incredibles over at Pixar.

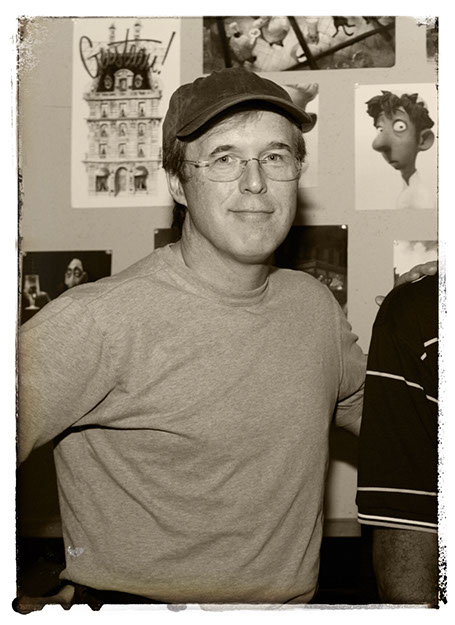

BRAD BIRD:

Oh, absolutely! It’s a film that I’ve been wanting to make for a long time.

I hope you won’t mind but I want to skip pass that project. I see The Incredibles as an autonomous work, something of your own design, and not one of the ones where you peered into something damaged, for lack of a better word, and salvaged it. I say that appreciating that The Incredibles is a great film, a progressive comic book movie and a genre film like so many of your other works. But a lot this interview is about fixing things and not about auteur works. So, I want to skip to your work on Ratatouille. Was being brought in on Ratatouille in any way a response to people at Pixar seeing what you stitched together out of the failed live action adaptation of Pete Townshend’s musical The Iron Man, and how was your ‘repair’ work on Ratatouille similar to working on The Iron Giant?

BRAD BIRD:

Well, for me, this isn’t new. I’m part of a group that goes up to Pixar and goes through all the films. I looked at [Finding] Nemo or Cars, or any of the other ones. We kind of look over each other’s shoulders all day, the directors and writers there. We’re fresh eyes to each other when we get a little too close to our own work, and we’re kind of brutal with each other in a nice supportive way. We’re also very honest and say things like “Well, I don’t understand what this character is thinking at this moment.”

So when they hired me [on Ratatouille], John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton knew I was behind the eight ball and they basically said they’d help in any way they could. But they also knew they couldn’t give a ton of notes, because we really had to get this thing into animation. So let us know where you want to focus. We’ll be around as much or as little as you need us. Because the time to give notes had already been used up.

So I had to move and it was actually a shorter time for me to be involved on Ratatouille than it was for me to be on The Iron Giant.

Initially, what were your thoughts about Jan Pinkava’s version of the film (the man who originally directed Ratatouille)?

BRAD BIRD:

When I started, I was like a mechanic looking at a beautiful car that was somehow not driveable. It’s beautiful and the seating is wonderful and the motor is powerful but it’s not moving down the street, you know. So you’ve just got to lift up the hood and make your best guess at what the problem is.

There were really funny ideas that Jan [Pinkava] developed, and by the way, I really hated the idea of taking over somebody else’s dream project because I have a lot of respect for Jan and I think he’s very talented. It was a rough position to be in because I always come down on the side of the creator. I want people who come up with the idea to be the ones who usher it all the way through.

But the project was having trouble and I also have a lot of respect for the entity of Pixar and [John] Lasseter and Ed Catmull and Steve Jobs and Andrew Stanton, and the heads of Pixar asked me to come in because the project was in a rough position. And this was after years and years and years, so, you had to do something because the train was ready to leave the station so that’s kind of what happened. So I took one for the team because [Pixar] is such a rare, rare place. They were in a bind and Jan’s concept was a good idea.

At the head of our conversation, you referenced your friends working at Disney and how they chose to work inside at Disney as co-directors, working on projects Disney was interested in doing, like fairy tales that had songs in them and films that had animals as its lead characters. That these were the sorts of films the suits at Disney were getting ‘the rabbits who work in the warren,’ as I like to say, to make. As it works out, Ratatouille has no songs in it but it is a film with animals and humans in it, and yet how you tell a story with animals and humans is more like a live action feature film than let’s say The Fox and the Hound (1981), a film you worked on. Isn’t that key, and maybe what the executives back in the day were unable to see about you? How did you go about thinking about how to work with a film narrative in this way?

BRAD BIRD:

People criticize feature animation for being too literal or not cartoony enough. But that comes with the territory [when you make a feature film]. If you watch a great Bugs Bunny short, it’s an exhilarating thing. You wouldn’t change it. It’s perfectly calibrated for seven minutes. But if you watch two hours of Bugs Bunny cartoons in a row and you’re not just an animation fanatic, if you’re let’s say a normal person, you get tired after a while. Your eyes get tired. You start to become desensitized to the pace and the chaos and all of that. And, you stop being a good audience for all this amazing stuff.

Believe me, I love animation. I’ve sat through the Warner Bros. [Looney Tunes] collections long before they were available on home video. If somebody would run two hours of Warner Bros. cartoons non-stop, I hated the fact that I got worn out. But I did. A movie audience did, too. They did not laugh in hour two the way they did in the first half of hour one. That’s because the films are calibrated for what they are - seven minutes in length.

When you go to a feature length, you have other things you need to give to the audience. They have to start believing in the characters more. There has to be a suggestion of a life outside of what you’ve been seeing. Outside of the setup for a gag. Now, I would never say “never.” There is probably some perfect Airplane-type animation movie that has not been made where it never gets serious. It never gets emotional. Look at how many live action comedies have come out and how many of them fail. There are only a handful of films like Airplane that manage to sustain their comedy and their sincerity for an hour and a half and keep the audience with them. It’s a very tough thing to pull off.

Well, that speaks to the dycotomy of it, doesn’t it? Disney has had a long legacy of bringing in talent like Oskar Fischinger or Kay Nielsen, or Mike Mignola in more recent times to invigorate invention, and inspire something new among the staff. But companies in general sell the same old formula, and not something outside of the box. Isn’t that why the use of comedy is the same?

BRAD BIRD:

Well, I feel like people, it’s easy to be a critic of feature length films for the “Hey, they should be zanier or whatever.” It’s like, you know, knock yourself out. If you see the way to go do it, then go do it and I will be first in line.

As it works out - me, too. It’s why I’m first-in-line when your films came out and why I wanted to do this interview. Because the road less traveled isn’t always the one that’s easy but more times than not, it is the one that gets you the greatest applause.

To read more about Brad Bird and his work on Ratatouille,

please refer to this older interview with him that can be found at this link below:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille

Images are owned by © Disney/Pixar.

The author would like to thank Jim Walker, Irene Rosignoli and Dan Sarto for their help.

Additional thanks goes again to Kelsey Donofrio, Christine Foy and Ralph Eggleston for their efforts to make this publication happen.

This article / interview is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.

© Disney Enterprises, Inc. and Pixar Animation Studios

BRAD BIRD's Amazing Story,

from leaving Disney onto fixing The Iron Giant, and the Road Less Traveled

© 2018 Ron Barbagallo

PART OF the Lost and FOUND series FROM

THE RESEARCH LIBRARY AT ANIMATION ART CONSERVATION

You’re young. Out of college, in your 20s — full of animated hopes and directorial dreams. You’ve landed your first grownup job at a major studio and you couldn’t be more excited. You’ve waited a lifetime for this, and yet the place you’ve landed feels confrontational in ways college did not. It feels like people around you are threatened by what you do. Jealous of your passion and your focus, like holding you back, or copying what you do somehow pushes them forward. What do you do?

Dashed expectations in Hollywood are par for the course. It’s something that’s affected the careers of anyone with any talent, and something that effects the ones with real talent the most. For animation professionals with any drive, the problem is inevitable. So is learning how to maneuver around these roadblocks. Mastering that lesson will prove more practical than anything you can learn in a classroom, and the place to start is by examining the career detours of people who have come before you. People like film directors John Lasseter and Tim Burton, Pogo creator Walt Kelly, Dennis the Menace creator Hank Ketcham, Looney Tunes production and background layout designer Maurice Noble and two time Academy Award® winning motion picture director Brad Bird to name a few. Every one of them came to Disney in the beginning of their careers, and every one of them had to leave so they could prove their true worth.

Career forks-in-the-roads like these present such teachable moments, and that’s why in 2007 I spoke with film director Brad Bird about the early part of his career and the road less traveled.

I wanted to know how after a short tenure at Disney, a place he left with an explosion reminiscent of a 10 gallon bottle of water careening down a flight of stairs, Brad Bird went on to receive an Academy Award® for his work on Pixar’s Ratatouille. This interview focuses exclusively on the time between those two events. It was designed to play like an episode of Iconoclasts on the Sundance Channel — a “how-to” dialog between a man who repairs Disney Animation Art and a Film Director who has repaired so many Animated motion pictures and TV shows. A look at a drawback all too common in Hollywood, this interview with Brad was stashed in the vault of Ron Barbagallo’s Research Library at Animation Art Conservation for a decade. It is the third lost and FOUND entry from Barbagallo’s Research Library. September 2018 marks the interview’s first public debut.

Good afternoon, Brad. How are you?

BRAD BIRD:

Good.

Great. Let’s get to it. Your career is an interesting one to me. When I speak to animators, or anyone working in animation in a way that involves design or craft, your name is the one name that always comes up. More frequently than anyone else. When they tell me about their projects and pitches they’re working on for the films they want to make, they often tell me they want to be like you. My advice to them is to study your career path.

BRAD BIRD:

Wow. That’s probably dangerous to say because my career path is very long, very delayed and full of disappointment.

Yes, but it’s also full of high points, and I think many people’s careers have their peaks and valleys, and Hollywood is a place full of people pitching projects, people asking for things. It’s also a place where people with power try to marginalize and limit other people’s power. It’s why I like to advise people that it’s best to know what you may ask for when you decide to extend your hand. Because if you ask for something too lofty, you’re likely to get your hand slapped.

BRAD BIRD:

Well, you’re talking to a guy who was constantly asking for lofty things. Things that were considered crazy. I mean, I was supposed to make an animated feature based on [the Will Eisner comic book] The Spirit a long time ago, and at that time, I was told no animated film would ever make more than 50 million dollars and the only ones that even came close to 50 would be from Disney. That was the kind of prevailing wisdom I was dealing with and my subject material was an obscure comic book from the 40s that had nothing but humans in it. A superhero without superpowers. It didn’t matter how good our work was. I was trying to make animated features outside of Disney which was considered insane at that time. At that time, what I was pitching was reasonably priced, too.

So instead you could make a very good case for doing what most of my friends did which is go to a place like Disney and be a co-director and do whatever projects the company was interested in doing, fairy tale films with songs.

My way of doing it took a lot longer for me to ever get a chance to direct and for every good project I’ve made, I’ve got equally good projects that are sitting in the bowels of various studios. So I would hesitate to hold me up as a role model because it’s a very rough path that I took.

But let’s talk about that path.

You were at Disney, early in your career, and then you left. The next thing I recall seeing your name on was an Amazing Stories episode called Family Dog. How did you get that Amazing Stories episode off the ground?

BRAD BIRD:

Well, when I realized that Disney was not going to be the place that I thought that it was, I had two alternatives. One was to quit animation and go into regular live action filmmaking, and the other was to make one last shot at doing the kind of projects I wanted to do in animation and see if I could get anyone interested in paying for it. I chose the latter. I took whatever money I had in the bank and I made a little sample film that I called A Portfolio of Projects. It had The Spirit on it, and I also put Family Dog and a couple of other ideas on it.

Tim [Burton] did the designs for the Family Dog, and it was a little 16mm film, basically sort of pencil test level stuff. Some of it had color artwork with the camera-kind of panning over it while somebody described the ideas. It was cut to music and stuff. Eventually, it caught the eye of [Steven] Spielberg. He toyed with it for a little while. But Family Dog was supposed to be a series of shorts and at the time, Steven felt there was no way to make shorts economically viable because the theaters didn’t want to pay for them. The economic model from the old days [the 1930s...50s] was not there anymore. You know, where you put a short in front of a movie.

Right, the studio had no system to attach a revenue stream to the film so they could recoup their costs.

BRAD BIRD:

Yeah, but you see, I felt like, and I still feel that there is. I just think that you have to view it in a different way. You have to view it more like the total value of a body-of-work rather than the individual short.

Like having a broader view within your business plan? Cost averaging the expense of making feature films AND shorts?

BRAD BIRD:

Yeah, in other words, the Warner Bros. Library makes them a tens of millions of dollars every year and they don’t pay anything for that. If somebody viewed it somewhat like they viewed a television series, where once you get a critical mass of, I don’t know what it is but a certain number of episodes, that they could put them into syndication and that series becomes a money machine. If you viewed shorts in that context, I think you can make a case for it. You’d have to make a financial model for it.

But in any case, nobody has bothered to do that, and Steven [Spielberg] let it go. It just sort of stayed in sort of a nowhere land for a couple of years and when I got involved with writing a live action screenplay for Amazing Stories [a Matthew Robbins directed episode called The Main Attraction, original air date: October 6, 1985, Season 1, Episode 2], Steven liked that script so much that he invited me to come down and he offered me some other things.

In the interim, Tim [Burton] had gone on and started his film career and I had written another Family Dog short. I storyboarded it myself. I brought it along with me when I came down to discuss other projects [with Steven] and he said, he looked at it and laughed, and he asked me “Could you do a half an hour of this?” So, I said “No problem” and he said “Let’s do this as an Amazing Stories.

The original Family Dog I had done was the one where Tim Burton had done the storyboards, most of those storyboards were done under my direction. That was the first one. Then there was this one, and another one called Prowlers that I wrote. That was the third one.

When we got into making the show [for Amazing Stories], the three of them together ran over length. My co-producer at the time wanted me to cut all of them down. But they were so tightly conceived. You would have ruined the comedy in every single one of them in order to make it run 22 minutes.

Rather than do that, I took out the initial one that had gotten Spielberg excited. We had begun that one, too. We did several layouts and recorded the sound for it. But we hadn’t done any animation or backgrounds or anything. I just pulled that one out and I conceived a new one to fill the gap [between the second one and the third one, The Prowlers.]

In other words, after I pulled out that original one, the total length of the show was like two minutes short. So I conceived “the home movie” one to fill in that gap. I knew a home movie format could expand or contract based on whatever length was necessary. This way I wasn’t cutting anything unnecessarily from the other two [Family Dog sequences]. Those two sequences were allowed to grow as much as they could grow and find their correct length and the home movie one was just a way fill up that gap. That’s what happened.

And the end product of all that is the episode that premiered Family Dog, the one that aired on Amazing Stories?

BRAD BIRD:

Right. There were essentially three short cartoons. There was one of average short length; that was the first one. Then there is the one that is of under-average length, which is the home movie. Then the one that is over-average length which is the one with the prowlers breaking into the house.

Outside of his work on the initial designs, the drawings that he did years earlier, how involved was Tim Burton with the episode that was done for Amazing Stories?

BRAD BIRD:

Tim did a few new designs when Steven [Spielberg] agreed to do the show. I asked [Tim Burton] if he’d be interested and at that time he was making live action films. But I told him we have these new ideas. Would you be up for designing a couple of new characters? So Tim came back and did a few drawings that we used for the designs of the two thieves and Gerta LaStrange who runs the dog training school. Tim also designed the two prowlers.

It was a day here, one day there. If you put it all together, the total amount of time that Tim spent working on Family Dog if you added everything together was maybe three weeks, over all the years.

So Family Dog really was your project to which Tim contributed some design work?

BRAD BIRD:

Yes, he did the drawings that were in the initial pitch. Still drawings of the dog and the designs of the family that were in the original Portfolio Project. Then he did probably 80% of the initial storyboards which I had done the thumbnails for, showing [Tim] where I wanted the camera. But Tim did the designs and we very much adhered to those designs when we made the show. We made the show like it was one of Tim’s drawings.

I want to skip forward a bit to your work on The Simpsons, a project that is archetypal of solid part of your career where you are brought on board to save a project that’s already developed but floundering, like The Iron Man (later retitled The Iron Giant) a live action version of the Pete Townshend musical over at Warner Bros., or Pixar’s Ratatouille. Were you the guy who altered The Simpsons and made its format more accessible to an American TV audience? The Klasky Csupo version done for The Tracey Ullman Show, the design of the characters are more aberrant, the pacing of the series frenetic and so European. I was wondering if you were the guy who came in, added The Flintstones or The Honeymooners structure to it and made it into the series we know today?

BRAD BIRD:

I was one of the group [of people] that contributed to that [transformation]. I was not involved in The Tracey Ullman Show. My work on Family Dog predates Tracey Ullman. But they [producers working on The Simpsons] responded to what I did on Family Dog and recognized that the show was a lot more complicated than one minute segments. What they liked about Family Dog was that it was stylized and that it had a cinematic sensibility that was not like most animation at that time.

[Executive Producer] James Brooks knew the kind of comedy that worked in two minutes was not the kind that could sustain a half hour show. His brand of comedy is much more cerebral, and funny at the same time and accessible, and character-based and all of this. But I think they were responding to the fact that Family Dog had high angles, and low camera angles, and really long takes which is not the case in most animation. Most animation tries to keep scenes short because animators get bored if they have to work on the same shot for too long, especially back when things were still on cels. It’s also much more difficult to shoot long takes because if you make a mistake it becomes much harder to deal with.

So there were all these rules that had to do with how producible things were and those rules started to limit or dictate the style of things. On top of that, many of the storyboard artists [from The Simpsons] were trained in this Hanna-Barbera Saturday morning school of always opening everything with an establishing shot. If people were moving you did it in a medium shot. It was all at eye level. If your characters were talking, you cut to whoever was talking in a medium close up. It was really ultra-basic. They were trained rigorously to do that because that kept TV animation easy to produce because it was all about volume.

Once they got me involved, I said we have TV schedules, budgets and we’re sending work to the other side of the world. We can’t really afford to do elaborate [character] animation. But what we can do is have really good filmmaking. So I thought since this show had a larger budget and complex scripts, so let’s make the filmmaking more complex.

How so exactly?

BRAD BIRD:

I decided to shake the storyboarding crew and directors up a bit, and said “This is kind of a Stanley Kubrick-like joke." Let’s look at some Kubrick’s work and when you come back to me tomorrow, you’ll notice everything was shot in a wide angle lens. A lot of times shots are symmetrical. So, let’s push the perspective because the show's reference points were wide and the comedy is often complicated; I mean the dialogs weren’t necessarily easy.

Could you explain that?

BRAD BIRD:

Yeah. People talk about how verbally oriented The Simpsons is and that’s true in many instances where the soundtracks are funny - just by themselves, like radio. But there are also a lot of visual jokes that are actually kind of difficult to pull off. The fact that nobody notices that aspect is because we pulled them off well. But there were things that writers would write that would be hard to pull off, and easy to blow, and so I got the artists to look at feature films, movies and wanted them to consider these shows hand-drawn miniature movies.

The storyboard artists were a little puzzled at first and then they took to it like ducks to water. They loved it and looked at creating really good filmmaking on the sort of schedule we had to get in by as a real challenge. By that point, we started to do things that were absolute no-nos in the animation industry, and for TV animation in particular. I’m not going to say that we were the first to ever do them. I think a lot of great shorts directors did these things. But we were the first ones in a long time to do it, well, maybe ever do it for TV where you had fast, rapid cuts like in a live action motion picture.

Why was no one doing this sort of thing in TV animation before? Can you give me a concrete example of what you’re talking about?

BRAD BIRD:

The reason nobody does that sort of thing is because every time you cut in hand-drawn animation you need a new layout, and TV is all about maximizing the work and minimizing the number of shots. If we did a parody of McBain [the Arnold Schwarzenegger-like, Die Hard type character] and something blew up, we would make fun of the fact that they shoot those things with multiple cameras. So we would do 12 different layouts that we would blow through in two or three seconds.

People really responded to it. Production people didn’t like us because we made the episodes more difficult to produce. But the jokes were on a level people hadn’t seen. It was really fun and I learned a lot working on The Simpsons.

There was a lot of the pressure to get these very complicated and sophisticated scripts done. 24 of them a year at the height or more, and that meant you had to move and make decisions quickly. That saved my butt in all three of the feature films I’ve done, especially while working on The Iron Giant and on Ratatouille. Both had very short schedules by the time I got involved with them.

Regarding The Iron Giant, that was one of those projects similar to 1906, (the failed Barry Levinson film) where after a long time Warner Bros. removed Levinson as that film’s director and hired you. Was your time turning The Iron Man into The Iron Giant brief?

BRAD BIRD:

Iron Giant was a very short schedule for an animated film. I was involved for about a year an a half. No. Two and a half years from my outline to the finished film on Iron Giant, but that was everything. You know, boarding it, designing it, recording it, animating it, finishing it. All that stuff.

When it comes to these ‘broken’ projects, you seem to have a really strong sense of how to find the broad message inside the flawed story they show you, and how to remove the parts that are holding the narrative back and how to replace those flaws with characters and storylines that support a narrative you want to tell. One that resonates. Your ‘fixes’ never feel obvious or inserted. Sometimes your films contain a moment defined by a quick two or three shot of something that creates character. Other times, you’re playing to something broad and universal like the way characters relate. This is why your films move from scene-to-scene without anyone noticing. That’s your gift.

BRAD BIRD:

Wow, thank you.

Many times, after The Iron Giant, came out, when I’d be at a meeting at Warner Bros., and some of the suits were talking about who they could get to direct a live action version of Superman, I’d tell them the guy they ought to consider is Brad Bird.

That you understand genre films very well, and more importantly - you like them. You are also able to make those type of characters in genre films real and completely accessible. You also understand storytelling in a way that most people who direct animated films do not. In that way, your films are more like the work of film director Billy Wilder. You also understand women, and the men who like women in a way that feels real and connected. Since Superman is basically a film about a man trying to impress a woman, for me, you seem like the obvious choice. You’d understand the human side and the time period, and that at its heart, Superman is a love story and a story about attraction and what a man is willing to do for a woman. It’s not about revenge.

BRAD BIRD:

Wow. Again, thank you.

Brad Bird's Amazing Story, from leaving Disney onto fixing The Iron Giant and the Road Less Traveled

was reblogged by these Online outlets:

INDEX OF SERVICES

The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

the Lost and FOUND series

RON BARBAGALLO: